Jia Yinzheng works at his studio in Xiaoyaotou village in Taiyuan, Shanxi province. [Photo/China Daily]

Figurines representing local legends, folk culture are popular with residents in Taiyuan

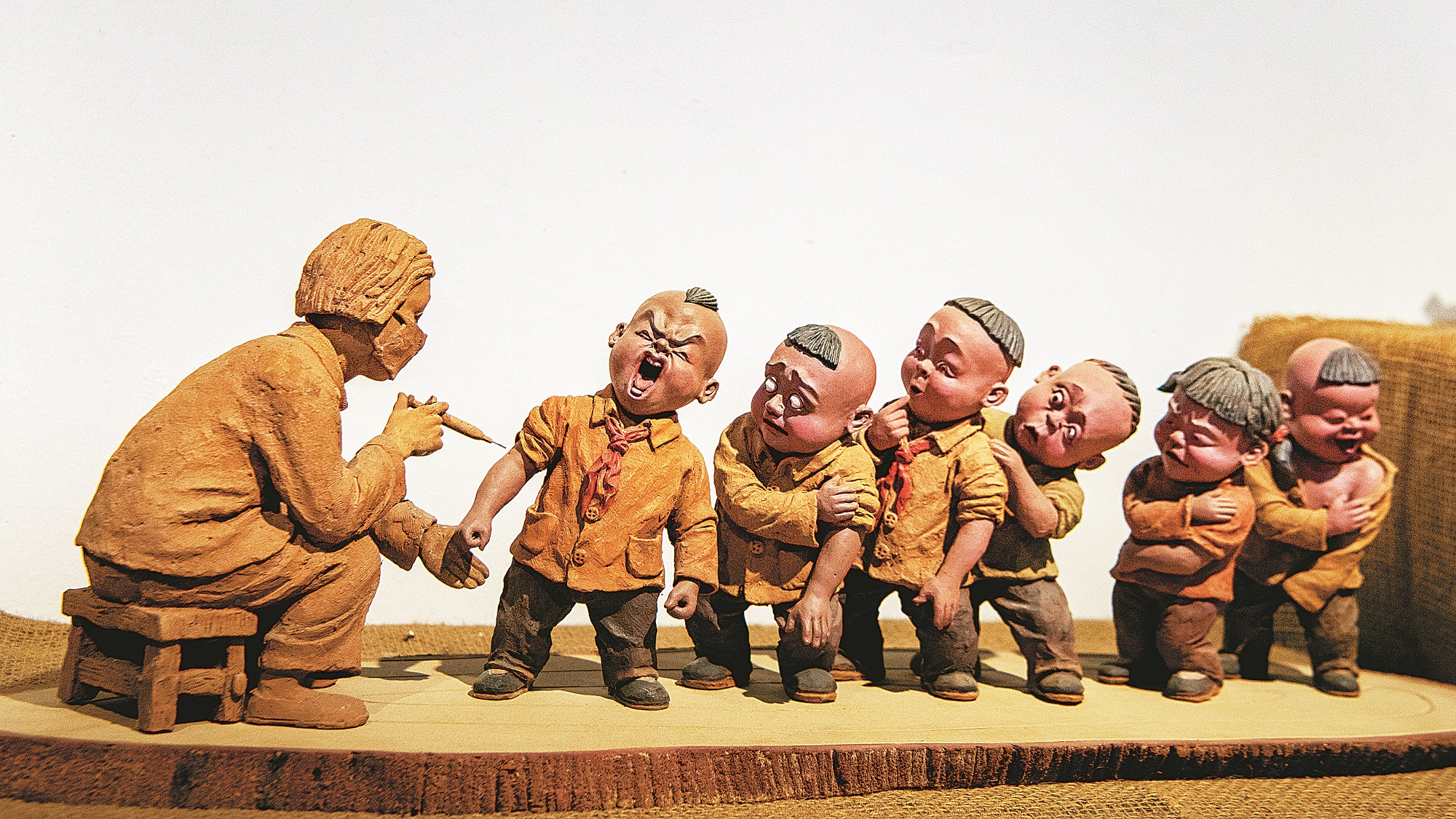

In an ordinary courtyard in Xiaoyaotou village in Taiyuan, capital of Shanxi province, a series of miniature live-action scenes made using clay sculptures, ranging from nervous children waiting for a COVID-19 vaccine to old men staring intently at a chessboard, are on display.

Sculptor Jia Yinzheng, an arts and crafts master in his late 30s, is the director of these clay stage plays. Locals call his home a neighborhood museum.

A wooden knife is all he needs to bring his lumps of clay to life.

After he's finished, the figures have their own character, mood and stories.

His work is delicate, as he pays a great deal of attention to adding vivid expressions and exquisite details to his works.

Jia's clay figurines represent characters in Shanxi legends and folk culture, which makes them popular with local residents.

Part of one of Jia's clay sculptures, Shehuo (a traditional folk show) in Qingxu County. [Photo/China Daily]

Clay sculpting dates back to the Neolithic period, and China's own version of the Adam and Eve story is that it was the goddess Nu Wa who created humans out of clay.

"Clay has a special meaning to Chinese civilization, which is believed to have originated in the middle reaches of the Yellow River," Jia said.

Born in Qingxu county, Taiyuan, in 1983, Jia is the fifth generation of his family to work with clay. When he was young, his father would give him clay toys he'd made, and one of Jia's favorite childhood pursuits was making miniature clay sculptures of cats, dogs, pigs, sheep, and even household objects and furniture.

In 1999, he enrolled at the Yangquan Culture and Art School and began to learn painting. After graduating, he attended a training course for advertisement design at a private school. Jia worked as an advertising designer in Taiyuan until 2008 when by chance, he met a folk artisan earning his living by making clay sculptures for temples. The artisan encouraged him to pursue the trade after learning about his family background.

"The clay objects my father made were mostly things like tumblers and whistles-things you could use," Jia said. "But learning to make sculptures for temples pushed me closer to my childhood dream of becoming a sculptor."

When he was 26, he quit his job and started to learn how to sculpt Buddhas. Training under the artisan reignited his interest in the craft.

The artisan had 20 apprentices. Jia was the oldest, and although he was the last to join, his father and other family members who were clay sculptors had given him a solid foundation.

Jia's clay sculpture work, Clean Ears. [Photo/China Daily]

The master was strict with his trainees. At first, Jia was assigned the most tiring work, that of preparing the clay, and was not allowed to do anything more advanced-not even simple tasks like polishing the clay.

In fact, he didn't learn any skills or techniques for three years, by which time observation had given him the knowledge he needed to learn more advanced techniques and skills. The master would often tell apprentices that the process of training a sculptor was similar to the process of making a sculpture. It first required good quality raw materials, like the clay (the basic skills), and then needed to be formed through proper modeling, polishing, and painting (the advanced skills).

When his son was born in late 2010, Jia bid farewell to his master and began to work on his own making clay figurines. This is when he met his most important teacher, Fan Yongliang, a master of clay sculpture-making.

"He felt like an old friend from our first meeting," Fan said, recalling his encounter with the young man. "It is more accurate to say that I am both his tutor and his friend."

Fan felt it was important to give Jia the guidance to ensure that his talent, skill and passion for the intangible cultural heritage could later be passed down to future generations.

As a result of Fan's tutoring, Jia made quick progress, both in terms of his ability and his creative concepts. He began to tell stories from his hometown's history by using clay figurines in vivid clay settings.

One of his masterpieces, The Return of the Shanxi Merchants, consists of nearly 160 miniatures, including camels, bodyguards, merchants, horses and goods. It portrays the hustle and bustle of a company of traveling merchants returning home from the region north of the Great Wall during the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Jia's work, I'm the Next One to Be Jabbed. [Photo/China Daily]

Jia has also recreated childhood memories and said that the simplicity of life in 1980s China is a source of nostalgia for an entire generation.

Commentators say that the unpretentious nature of clay makes it a perfect choice for conveying the period before the country's economic rise, when people were full of hope for the future and still able to enjoy the simplicity of interpersonal relationships and a more austere way of life.

After winning a couple of national prizes, Jia has become a well-known artist and no longer has to worry about making money.

Three years ago, he moved his studio to Xiaoyaotou, where the city government has provided workshops for over 20 intangible cultural heritage projects. The village has become a tourist attraction. "I am happy to see so many young people come to the village to learn traditional crafts," Jia said.

More importantly, when the younger generation see that craftsmen can make a decent living, they become more confident in the future potential of arts and crafts and are more willing to become craftspeople themselves.

As his master told him once before, the pursuit of perfection in traditional arts and crafts is infinite, and their future always lies with the young.