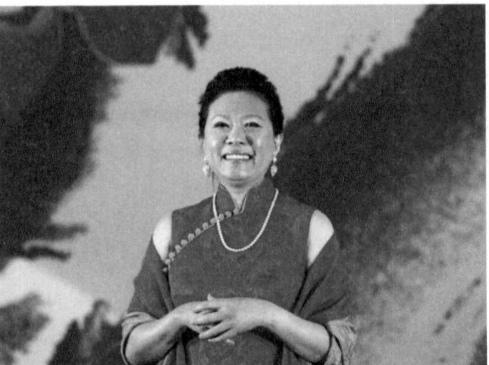

If hard work, resilience and determination are key characteristics of the people described in this book, then Cecilia Yeung should really be the protagonist. A single woman in her fifties, she has the energy of a teenager. When Cecilia hosted the delegation of which I was a member when I first landed in China in 2003, she was the first TNT employee I had the privilege of meeting. Having joined TNT in 1992, she represents an important part of the collective memory of the organization in China. With her‘elephant skin’ and heart of gold, she has managed to survive all the changes. She may be the only micromanager I have ever learned to appreciate deeply.

Cecilia is the daughter of Brother Yat (his full name is Yeung Koon Yat), a famous restaurateur from Hong Kong. Cecilia’s life story cannot be fully understood without an intimate reference to her father’s. Brother Yat grew up in Zhongshan in Guangdong province. Two of his sisters died of starvation. These tragic losses served as continual motivation for every member of the family to work hard and make sure everyone had enough to eat.

Brother Yat came to Hong Kong in 1949 with very little money. His future wife, who he knew from Zhongshan, also came to Hong Kong that year, and they married in 1950. For the next 27 years Brother Yat worked as a waiter in various restaurants. He and his wife had three children-two boys and Cecilia, their middle child. It was not until after all those years of hard work that Brother Yat made a name for himself by inventing a special way to cook abalone. He became a famous cook with that recipe. He now owns numerous successful restaurants across Asia.

Poverty and its associated challenges and disappointments marked Cecilia’ s childhood years. The family had barely enough money for subsistence, and when he r father got sick for a period of time, they had to live with their grandparents in Maca u to survive. Brother Yat worked 360 days a year-every day until 22.30. Often he would live next to the restaurant where he worked. For years, Cecilia saw her father only sporadically, but her mother was a strong, independent woman who kept the family going.

Her family’s meager income did not allow Cecilia to begin school right away. She remembers looking outside of their apartment window at the kids enjoying the school next door-how wonderfully happy every child looked! One night, Cecilia overheard her parents discussing how they wanted her to attend school, and she dreamed about going to the school next to her house. When she finally joined her school, on the third floor of a run-down building, she was disappointed-but at the same time excited that at last she could go to school. However, because she was two years older than all the other children, she felt very uncomfortable. After entering primary school, at first she found it difficult to catch up with the other children. She had to repeat fifth grade, increasing the age gap with her classmates to three years.

Although perhaps unintentionally, Cecilia’s family provided her with very little support in her studies. Her mother had not received an education, and though her father supported her going to school, as previously mentioned, she only saw him briefly in the mornings. Nevertheless, by the time she reached high school, Cecilia had gained confidence and her grades improved. She won a few awards and even became class representative. However, during 10th grade she spent most of her time in church-Cecilia is a devout Christian-and she had to repeat again. She finally graduated from high school at 23 years of age.

Because her chances to go to a university had passed, Cecilia found a job as a clerk. She made money on the side teaching children’s history classes. Just like her father, she worked every day until 22.30, yet she found her work fulfilling. Although she found inspiration from her religious faith, after working for two years Cecilia decided she needed to have a better education in order to improve her life. Her mother thought going to university at age 25 was a crazy idea, but her father supported her, and because of her determination, one professor was willing to give her a chance. For Cecilia, admission to university confirmed her equality with others.

During her second year of university, Cecilia was offered a good job in the Housing Department of Hong Kong. Her mother encouraged her to drop out of school and take the job, but her father encouraged her to persevere in her dream of graduating. She stayed in university and graduated in 1984. She decided she wanted to go to mainland China, because she believed very good opportunities awaited her there.

After moving to Beijing, Cecilia found a job as an assistant for the Chinese consultants to the Dutch aircraft manufacturer Fokker. Through this position she met the Dutch sales director of Fokker, who came to China regularly. She helped him with translations and all sorts of practicalities. This sales director became an important person in her life; he was the first to really recognize her potential. She very much enjoyed seeing China while traveling around the country to sell aircraft.

Following her stint at Fokker, Cecilia held a few other jobs with consulting and trading companies. In these various roles, she saw a lot of China, including the countryside. She observed first-hand just how poor many people in China still were. The fact that her work in the trading business allowed her to contribute to China's development really encouraged Cecilia. She felt strongly that in addition to providing a living, her work should be deeply meaningful and really make a contribution.

In 1992 Cecilia applied for a sales job with TNT in Hong Kong. Although she was only offered a job in Customer Service, she worked hard and excelled. Within three months she became head of the department; three years later, she managed all customer service teams in the region (seven countries total). Overall, the business was struggling, yet Cecilia enjoyed the challenge, and her career flourished. Her Korean boss sought her help for complicated tasks like restructuring the work of the sales teams. In spite of the internal political struggles associated with these projects, she still managed to succeed.

In 1998, the Netherlands firm KPN acquired TNT, still an Australian company, and Cecilia’s professional life changed yet again. The new leaders failed to recognize her record of success and didn’t realize her potential. She was sent back to Hong Kong to be the customer service director. This demotion almost caused her to leave TNT, but Cecilia confided that every time she gets really frustrated, she thinks about how she can improve herself, so that when new opportunities arise, she will be ready. Instead of quitting, she decided to stay and pursue an EMBA in her free time. She excelled in her EMBA studies, receiving the prize for‘best paper’ among her graduating class.

Soon after Cecilia completed her EMBA, TNT started to cooperate with China Post, the state-owned Chinese postal service. Cecilia was asked to move to Beijing to lead this project. She soon rose to regional general manager for the North region. Several turbulent years followed. The joint venture with Sinotrans was dissolved, and TNT embarked on various organizational restructurings in an effort to capture the‘big promise’ of China. (I began visiting China on a number of occasions during this time of upheaval.) The management team suffered a lot of turmoil during this period as more and more of them became implicated in integrity problems.

At this time, Cecilia was asked to move to Guangzhou and lead the South region. This was just prior to Michael arriving in China. She spent the first few years‘cleaning up’ the organization by dealing with many entrenched integrity issues. She gained the respect of the staff when she fired the Hong Kongnese general manager of the Zhuhai depot for his apparent role in the integrity lapses. By sending him away, she demonstrated her sense of fairness to the organization.

2008 turned out to be possibly the most difficult year for Cecilia. Her team had slowly come together, but they were not yet seeing the results of their efforts. Unfortunately, they failed to meet a very tough budget. At the annual conference early in 2009, Cecilia’s South region received no prizes. Cecilia told me later that she felt awful about this lack of success. But her team supported her, even sending her flowers after the conference.

However, in the years that followed 2008’s disappointing finish, the South region’s results improved dramatically. Their business grew even faster than in other parts of the country. They worked extremely hard, but no one put in more hours than Cecilia herself. When in early 2010 the South region won the prize for‘best region of the year,’ she stood on the stage with tears in her eyes; that moment represented a huge victory for Cecilia and her team.

When Cecilia told me the story of her remarkable life, she concluded, ‘I was laughed at by many people in my life, but I persevered.’

THE ABILITY TO CHANGE

When I came to live in China in 2007, of course I remembered Cecilia from my visits a few years before. By then, she had a reputation as an 'iron lady.' She was known for her enormous dedication and unbelievable micromanaging style. She literally made every decision, large or small, important or not, in the region. Compared to her, even Andrew Yang in the North was a strong delegator. Additionally, she was famous for never spending a penny.

In all honesty, I really could not understand how she had been able to survive. At that time, corrupt managers and awful financial performance characterized her region. As the head of sales and marketing, I noticed several opportunities for improvement in her region. Pricing schemes, the sales process, incentive structures-these issues as well as many more were all a mess. I certainly did not initially exclude the option that by the time I became general manager, I would have to let her go-or at least find her a more suitable job with less responsibility. However, one characteristic about Cecilia made me hesitate; regardless of any weaknesses she may have had, she could at least be trusted. Through all the integrity issues her region and the rest of the company endured, Cecilia had always chosen to remain honest and make the right decisions.

When I became the general manager and her direct boss, I had a frank conversation with her. I described her reputation with Michael and me: overly controlling, micromanaging, penny-wise but pound-foolish, and not very motivating for her employees. This last bit of information I based mostly on the fact that we continued to hear that people working on her team were being pushed to exhaustion.

Her reaction to my honest appraisal was remarkable. She told me that for many years, no one had ever given her any feedback. She hadn’t had one conversation with her superiors about how she was performing or leading her team. She simply assumed that by surviving all the changes, she was doing fine.

Although I had initiated our conversation fully intending to let Cecilia go or at least demote her, she seized the chance to demonstrate her willingness to listen and consider other ways of working. Stunned, I decided to give her another opportunity. I spoke with Michael, and although he supported my decision, he did not believe Cecilia would be able to change her leadership style.

Cecilia was always cautious about expressing her opinions in management team meetings, and if she did, she usually expressed them by asking tough, yet very practical questions. During every conversation about improving the customer experience, she always asked questions about exactly how she should improve that. She really wanted the manual with all the specifics-but she was certainly willing to write it herself if necessary. I realized that in many ways her convergent perspective provided a great counterbalance to my preference for the 'big-picture." However, I remained concerned that her fixation on the details could impede bringing our vision to life. Could she really engage the hearts and minds of her people, and through them engage our customers?

I reinforced my decision to give Cecilia a chance by showing her respect for her years of experience. I announced to the management team that whenever I had to be absent, she would act on my behalf. Additionally, if I had to leave the management meetings early, she would preside in my place. For a number of reasons, this decision worked out very well. First, I had chosen the person who according to Chinese culture deserved the leadership role (the eldest). Second, I had chosen the person least likely to compete for my role. Other management team members were clearly better positioned to succeed me; in this regard, Cecilia remained neutral. I believe she interpreted my decision as a sign of real respect.

Over the course of a year, I experienced first-hand Cecilia's enormous ability to change, no doubt made possible by the many times in her life she had had to adapt already. Previously, her authoritarian style simply resulted from how she interpreted her bosses’ expectations for her to‘be in control.’She began to understand that by controlling everything, she communicated a lack of trust, creating an unhealthy environment where people couldn’t learn to make their own decisions.

During Cecilia’s metamorphosis, I noticed that although a number of her team members had a really hard time working for her, the ones who had managed to accept her approach were actually very loyal to her. Their loyalty revealed a softer, more humane side of Cecilia. When her finance manager, a woman in her early thirties, lost her husband, Cecilia and her team surrounded her with care and support. A real tenderness shined through Cecilia’s tough exterior.

The contrast between the‘old’and the‘new’Cecilia was stark. When I attended one of her reviews in early summer of 2008, Cecilia crammed us all into a tiny, hot room in an office at the airport (a cheap location!), and the entire day she did all the talking. The event was awful; we all left the room exhausted, and I also felt very frustrated.

Two years later, Cecilia organized a similar review in Zhongshan (where her family roots are) in a new resort hotel. After her brief introduction, Cecilia handed the meeting over to her team members, who each displayed their knowledge and passion for their areas of focus. They were clearly in command of their responsibilities and confidently shared what they had achieved as well as what still needed attention. After the meeting we enjoyed some fun team activities followed by a lovely dinner with the Zhongshan depot staff, who entertained us and a few customers by performing some skits and plays they had prepared.

I really appreciated witnessing Cecilia's amazing transformation. Although I may have been a catalyst, my role was minor. Cecilia had made the necessary connections in her own mind and had decided to forge a new path. Members of her team later confirmed an abrupt shift in her intentions. She had told them very candidly that she wanted to change how she was leading them. She planned to give them more latitude and trust them more. Her team responded to this empowerment very well. They took ownership of their decisions and became accountable for the consequences. They were eager to show Cecilia and everyone else that indeed they could be trusted to act responsibly.

To an outsider, Cecilia’s change may not seem very complicated. After all, she did not need to master a new discipline or learn a new technical skill. She had‘simply’ learned to do a bit less of everything she did. Her team rewarded Cecilia’s courage in breaking‘new ground’ by managing differently. They were all eager to demonstrate that they would not spurn her gift to them. The two years that followed (2009 and 2010) became the most successful ever for their region. Their business grew faster than all other regions, despite the market challenges that South China faced when a lot of industrial production moved to West China. Their accomplishment rested almost entirely on greatly improved customer and employee satisfaction.

THE PEOPLE ON THE BUS

In his widely-acclaimed book,‘Good to Great,’Jim Collins makes the argument that great companies put the right people in the right positions-he calls this 'putting the right people on the bus.’At the same time the‘wrong people have to leave the bus.’Cecilia’s story made me question the wisdom of Collins’ advice. Initially, she wouldn’t have fit on‘my’ bus-I was not impressed with her intelligence at first, and her leadership style was exactly the opposite of mine. However, Cecilia did fit on our 'new bus.’and without changing her seat. She adapted, and we adapted as well. I adapted by not forcing her to become a different person altogether. Compared with other managers, Cecilia remains a‘control freak,’and she will still not spend a penny more than required. But relative to her past behavior, she has completely changed, and her flexibility has given space for others to grow. She had already earned the respect of many members of her team, and by entrusting them to perform, in their own way, she reaped their potential.

I have therefore come to believe that successful managing does not depend solely on putting the‘right people on the bus.’I believe the atmosphere and energy on the bus are equally important. A shared belief in the right direction for the bus and strong connections among the people on the bus are paramount.

In his amazing lecture,‘Really Achieving Your Childhood Dreams,’Professor Randy Pausch claims that if you have not yet seen the talents of the people with whom you work, then simply wait-their talents will be revealed with time. How refreshingly different this view is from prevailing management theory and practice!

Once I gained these insights regarding people’s inherent potential, I have witnessed many other surprising come-backs and turnarounds. Perhaps none were quite as dramatic as Cecilia’s, but indeed, given the chance to respond to honest feedback and the time and space to adjust within their own capabilities, most employees can produce remarkable achievements. This more optimistic perspective helps solve the constant puzzle faced by middle managers regarding under what circumstances letting employees go becomes necessary. Leaders must reach and maintain the high levels of performance necessary for business success, and accomplish this on time and within budget. Managing the personal stress of this responsibility represents a fundamental challenge for general managers. But leaders with a compelling vision must also embrace honest, transparent communication to create an organizational climate where their employees thrive and the enterprise benefits from their natural variety of talents and skills. As a rule, I don’t let people go unless they break the rules of integrity. To continue my paraphrase of Jim Collins’ metaphor, ‘Once you’re on the bus, I will make every effort to keep you on, as long as you contribute to our direction and a positive atmosphere.’

TO BE CHINESE OR NOT-WHAT IS AUTHENTIC?

An interesting additional side note to Cecilia’s success relates to the exceptional trust and respect given her by the mainland Chinese with whom she works-even though she is from Hong Kong. Let me explain. Many foreigners consider all people of Chinese origin to be‘Chinese.’I have learned that‘Mainland Chinese’do not share this view. Instead, they recognize all sorts of gradations within Chinese heritage. Here are a few examples: some Chinese were born in China but lived abroad for many years before returning (‘returnees’like Andrew Yang); other Chinese have lived abroad and acquired a foreign passport (many of them Canadians or Australians, also called‘returnees’), and still other people of Chinese heritage hold other Asian passports like Singaporeans. All of these groups are closely watched and scrutinized by the‘real’mainland Chinese for any sign of elitism-whether they behave as‘superior’Chinese.

The Singaporeans, Hong Kong Chinese and Taiwanese developed their economies earlier than mainland China; as a result, business owners as well as executives of foreign companies from these groups in China were often first to recognize economic opportunities in the land of their heritage. Professionally, they portrayed themselves as capable of‘opening Chinese doors’ to Western business interests. However, although they represented themselves as Chinese with a good understanding of the West, very often the Westerners working with them never realized that mainland Chinese regarded these self-styled liaisons as foreigners.

TNT offered no exceptions to these naive assumptions about monolithic Chinese heritage. When the management changed at the end of 2006, a large group of Singaporeans, Taiwanese and Hong Kong Chinese occupied all the key leadership positions. They collectively formed a‘glass ceiling’ preventing the promotion of mainland Chinese; they also effectively represented a barrier to real interaction between Western management and the Chinese staff. When I joined TNT, a number of these' outside-the-mainland' groups expressed explicit feelings of superiority. For example, when I discussed recruiting an assistant with the HR team (all Singaporeans), they very clearly advised me to hire a Singaporean to have any hope of finding someone in China who could adequately perform that job.

Of course, their ability to speak English represented the chief advantage that members of these more broadly defined Chinese groups brought to Western companies. Although simplistic, this single characteristic was often the key criterion foreigners applied when recruiting staff. However, the culture of mainland China differs dramatically even from region to region and, in general, from places like Singapore and Taiwan. As a result, although preferred by their Western recruiters, employees with backgrounds beyond mainland China often possessed only a very shallow understanding of China and Chinese people. To illustrate, many Singaporeans I have met over the years were not very eager to admit that in fact they spoke very little Mandarin Chinese.

Michael and I started to dismantle this glass ceiling, partly by coincidence and partly by design. A number of Taiwanese managers had been involved in some fraudulent schemes, so they were dismissed. The Singaporean HR team had earned a bad reputation for their elitism toward mainland Chinese in the years preceding our arrival, so Michael didn't hesitate to replace them. I dismissed a Singaporean sales manager with a drinking problem who abused her authority. She actually seemed to enjoy yelling at field staff members, and informed me that the excessive staff turnover, instead of being a problem, was simply a fact of life.

Encouraged by our willingness to replace key personnel with local Chinese, mainland employees gradually began to share their reservations about working for people with Chinese heritage who behaved as if they were superior Chinese. Some mainland Chinese even told me they preferred a Western boss to an Asian one of Chinese heritage. That was a real surprise to me. At the time, most companies I knew claimed to be on a path to localization (a commitment to hire local Chinese leaders) and the presumptive first step was typically to appoint a Hong Kong or Singaporean leader.

As I became more aware of the subtle, often unspoken resentment toward leaders of Chinese heritage who were not from Mainland China, I began to evaluate new hires not on the basis of where they came from, but what attitude they held towards China. Anyone expressing even a hint of the notion that mainland Chinese were poor and backward, and that China was a place to make good money (the Hong Kong Chinese and Singaporeans in TNT were often paid more than most Western expats!) were not admitted into our company, even if they came with the best documents and relevant experience. On the other hand, candidates with a deep connection to their heritage and a passion for China would be given the same opportunity as Mainlanders. Although at first these qualities were difficult to discern, over time my intuition improved.

My generalization here is not that only mainland Chinese can be successful leaders of Chinese employees. A number of other Singaporeans and Taiwanese became very successful in TNT. Gillian Pang, a Singaporean woman who joined China HR in 2008 to lead the learning and development team, became highly respected and trusted by everyone. Interestingly, when Gillian moved to Hong Kong to became TNT's HR Director there, she told me she found it much harder to integrate into Hong Kong culture, which she found to be more indirect, manifested by people remaining aloof even after she became acquainted with them.

Bryan Wei, a Taiwanese who had worked his way up from a menial job in the warehouse in Taipei to directing TNT's largest global accounts, worked on my team for many years; he was an excellent colleague and boss. I don't think we had any other director to whom the staff, most of them mainland Chinese, were more loyal. As a reflection of this devotion, I do not believe anyone from Bryan's team resigned during the four years we worked together.

Cecilia is perhaps the perfect example of a successful Hong Kong Chinese in China. She shared with me that she grew up with a strong sense of her Chinese heritage; she had only moved to Hong Kong due to circumstances beyond her control. When she had the chance, she returned to her roots to make a contribution. The time she spent traveling around China for her initial jobs reinforced this commitment. Although I noticed that Cecilia was always strict with her teams, she never exhibited any feeling of superiority. Perhaps her own struggles while growing up prevented the development of a sense of advantage; instead, the many challenges she faced must have given her the tenacity and humility that made her such a respected and trusted leader.

(selected from ln China, We Trust by lman·Stratenus, published by China Intercontinental Press in 2018)