On the third day that Linda Pan started to work with me, I asked her if she happened to have a pencil. She responded: “There are two in your drawer; I sharpened them yesterday.” I knew immediately I had begun a spectacular journey.

I arrived in Shanghai in January, 2007 to become TNT's Director for Marketing and Sales, a newly created position. Michael Drake had asked me to move from Vietnam to China. Michael himself had just arrived in China to lead TNT's business in the region. The business faced grave challenges, including slow growth, integrity lapses and high staff turnover.

I had to form a team and find an assistant. The HR team (all of them Singaporeans) assured me it would be impossible to find a good Chinese assistant; at best I could find a young graduate who would be willing to do the job for a year or so as a 'step' to marketing. They had a few candidates available with such intentions. However, HR suggested that I should speak to one particular candidate - just rejected by another director - yet who HR felt had potential.

I interviewed Linda the following day. Young and nervous, she spoke a bit like a computer. Sentences flowed from her mouth with such precision and in such impeccable English that it was clear she would be a perfect assistant for me. I like things to be organized, but I have a very hard time looking after the details of everything. Beyond her attention to detail, Linda indicated that her dream was to be a perfect executive assistant, because such a role fit her personality. I checked with the other director (from Hong Kong) to determine why he had rejected her. His answer was that he did not like the name, Linda; people who picked such a name could not be trusted. Astounded, I decided I was simply lucky in this case. I soon found Linda to be one of the most trustworthy individuals I have ever met.

Because Linda has been by my side since that first month, my China experience has been completely different from that of most other foreigners working here. Not only does she take care of everything, miraculously, she also understands how I think. She not only interpreted Chinese culture and social customs for me, she also skillfully represented my intentions and initiatives within Chinese customs and norms. As an important liaison, Linda helped me avoid many of the communication problems that foreigners face in China.

Linda arrives every day before I get to the office-around 7.30 am. She has never left before I do, even though I have tried many times to convince her to! I have never seen her in a bad mood. She has never taken sick leave and only takes a day off when I am outside China. If I ring her on Saturday evening to help a taxi driver find my destination, she answers and assists. From the hundred or so emails I receive daily, she keeps track of whom I have forgotten to respond to. Often, she sends me a text message at 6 am to remind me to bring my passport to the office. The travel summaries I receive from her include weather forecasts for my entire itinerary. In the last five years, she has only once sent me to the wrong place - and she apologized for over a week. Her nearness to perfection is simply astonishing. And those who know her will agree that I am not exaggerating for the sake of embellishing this story.

No doubt other brilliant assistants exist around the world who manage to improve their leader's effectiveness. But sometimes in an effort to protect their boss, they create more of a functional bottleneck around him or her than efficient and transparent communication. Not Linda. Instead, she spreads warmth and friendliness to all my constituencies, and a soft-spoken nature humanizes her perfect execution and attention to detail. She understands very well that she represents my personal 'brand; and she carefully protects that reputation. She reminds me to be attentive to people's birthdays and gives me a hint if someone has been unhappy or detached. She can push without being pushy. Over the years, many visitors to my office have started our conversation talking about my extraordinary PA-effective, professional and very friendly.

Linda was born in 1982 in a small town in Shandong province. Essentially neighbors from early childhood, both her parents came from families who had lived there for nearly 200 years. Her father’s family had enjoyed considerable wealth until her grandfather’s elder brother squandered all the family’s money on opium. Her grandfather joined the Red Army in 1945. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), he had returned to his home village, becoming head of the local tax office. Due to Linda’s grandfather’s ex-army status, his son, Linda’s father, was also entitled to a job in that bureau. He became an accountant there and remained in that position until he retired a few years ago.

Linda’s father was barred from any promotions because he and his wife had two children. Linda’s younger sister was born in 1985. When her mother went to the hospital to get an abortion, the electricity went off just as she arrived. She tried again a few days later, but again, all the power went off. Linda’s parents interpreted this as sign from the gods that their baby should live. With a monthly income of 20 RMB, they faced a 1000 RMB penalty. Now, Linda jokingly talks about her ‘expensive’ sister. In addition to the challenge of raising funds to pay that fine, her sister’s school performance fell below expectations, resulting in higher school fees for her parents. Linda’s sister remains very proud that her parents love her so much that they willingly endured all that inconvenience just for her.

Linda was always very close to her sister; in fact, they still share an apartment together. Her family has always been loving and caring. Her father was willing to sacrifice anything for his two daughters. When he couldn’t otherwise find a decent school for Linda, he sent her to live with an aunt in a nearby city. But after discovering that this aunt was not looking after her the way he wanted, he purchased a house in the city and bicycled to work an hour each way every day. The house cost 12000 RMB; for years, paying on this huge investment was all the family could accomplish.

Linda quickly learned that in return for all this sacrifice, she must work hard at her studies. As a rural girl, her chances of getting into a decent university were much lower than if she had been born in a city, due to the university allotment system. Her chances for a university placement stood around 10%, so her parents and teachers strongly encouraged her to study hard. She attended school 6.5 days a week (with only Saturday afternoons off), and on all six days her classes ran from 7 am until 9 pm. She studied only languages (Chinese and English), history, geography and social studies. During those years, she enjoyed no sports, arts, music-and only a few science classes. Little wonder that the Linda I became acquainted with is so diligent and hardworking!

In 2000 Linda graduated with the highest score in English in the Shandong province; for this accomplishment, her teacher earned a nice bonus. Linda also gained entrance to Shanghai International Studies University, where she studied English and Business Administration.

Moving from the countryside to Shanghai provided the biggest culture shock of her life. She lived in a dorm room with seven other girls, six of whom came from Shanghai. With 10 RMB per week to spend, she discovered a roommate of hers owned headphones worth 1000 RMB. She studied hard, and to make extra money, she tutored young children in English at their homes. Tutoring allowed her to become familiar with Shanghai's food, language and culture. Linda summarized it well:“All much more complicated than the simple life I came from.”

Linda helped one student in her early teens, under so much pressure to perform that she studied every day until 1 am and had deformed fingernails from practicing the piano. China's competitive culture is no fun for young people. Linda told me how fortunate she felt to have parents who encouraged her to work hard, but to a large extent shielded her from all that competition. “My parents told me to do my best, but I did not have to be the best. You have to cope with life’s challenges, but you don’t have to be tough on other people.”Her parents’ advice helped me understand why Linda was so nice and caring to everyone in her work environment.

In Linda’s third year in university, she tutored a child whose father introduced her to the CEO of a state-owned shipping company. Recently he had been humiliated by a really poor English translator. He needed an assistant fluent in English. Linda spent her last year in university-the year most students endure a lot of pressure to find a job-as a CEO’s part-time assistant. She easily secured a full-time position upon graduation. These circumstances made her very happy. She escaped the pressure to find a job, earned her ‘hukou,’ or legal residence in Shanghai, because she worked for a state-owned enterprise, and she found many interesting colleagues. Some old sailors worked there who shared many fascinating stories. She also earned a pretty good salary with a bonus and other benefits like travel opportunities.

While with this company, she had her first interaction with foreigners. The company shared important business operations with companies from Singapore and Norway, and Linda always coordinated the various necessary arrangements to support these relationships. She experienced no difficulties dealing with these mostly polite and interesting foreigners.

However, Linda faced one big disadvantage: changes in remuneration and promotions were based on seniority and relationships rather than merit. Although she started out as assistant to the CEO, after three and a half years she began reporting to an incompetent lady just promoted to finance manager. Linda decided to look elsewhere, and that's when she found TNT.

EMBARKING ON A JOURNEY TO CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE

When I walked into TNT’s Shanghai office in January, 2007, the only energy I felt was fear. People were almost hiding under their desks. Michael had arrived a few months before and had begun implementing what I think was the most crucial decision leading to the turnaround-he committed to local leadership teams by promoting mainland Chinese people. Prior to that, the entire management team of 15 people consisted of only Western and other Asian foreigners. Of course the people were skeptical that Michael and I, both Europeans, would be any different from what they were used to. But when Michael appointed a few mainland Chinese as replacements for the people who had to leave, and I started to appoint mainland Chinese in my sales organization, we gave them the first tangible signs of respect.

When we arrived, staff turnover was so high, it proved to be impossible to distinguish new employees from incumbents; anyone who had been there for six months would likely be the most experienced person on their team. People resigned for all sorts of reasons-not making enough money or being treated unfairly. In some cases people even resigned because they made mistakes and felt they lost too much face. When that happened on my emerging team, I seized the opportunity to tell the person that although he had made a mistake, correcting it was our joint responsibility. He looked at me in disbelief, but when he realized I was serious, he decided to stay. That story circulated around the office like a fire.

Michael and I had planted our first seeds to create a more trusting environment. But we knew we had a lot of work ahead of us. We had to face numerous operational, commercial and strategic challenges. There seemed to be no convincing differentiator for TNT in the competitive field at that time. I recall those first months in China mostly as confusing, frustrating and tiring. There was a pile of work to do and there was a real urgency to improve the results of the company. I had serious doubts whether we would be able to turn the situation around.

In 2007 TNT headquarters launched an initiative called ‘customer experience’, This initiative focused on implementing various programs to improve customers’ overall experience when dealing with our teams. Express shipping is a pretty complicated business in the sense that opportunities for mistakes abound. Just imagine how many people, modes of transportation, and technology systems must be integrated to bring a parcel from Shanghai to New York. Of course, every ‘hand-off’, every interaction, must be seamless to guarantee overall success. A team at headquarters embarked on programs to streamline all these processes, paying particular attention to the various ‘touch points’ -the steps in the process representing a human interaction between our employees and our customers’ representatives.

Even though‘customer experience’ was a new concept for me, these programs immediately made a lot of sense. Nonetheless, because we fell largely outside headquarters’ notice, China was not initially included in these projects. As usual, we were viewed as an ‘emerging market,’ mostly an afterthought behind the ‘key markets’ in Europe.

When Michael and I crafted our business strategy in 2007, our intentions fell far short of creating a compelling mission beyond the ordinary. Finances were bleeding; staff were still resigning faster than we could recruit replacements. We stood on a burning platform. We agreed to focus on what we did best-flying parcels from China to Europe. TNT’s board had just acquired our first Boeing 747 to support operations between Shanghai and Europe. Thus, we aimed at 'Becoming the leaders from China to Europe’. We surmised that this ‘customer experience’ concept could be useful to us, and we wanted to make clear that we would support programs from headquarters if only to secure all the help we could get! Therefore, in our first presentation to the Board in early 2007, customer experience already appeared as an overarching theme-but back then, we had little notion what it really meant.

During the following year, frankly, we did not develop the ‘customer experience’ concept very much. Instead, we worked very hard to fix more critical issues such as our pricing structure, and particularly the way our human resources functioned. In what turned out to be a crucial decision for our successful transformation in China, Michael fired the entire HR team. We hired new people, mostly from mainland China. Building on this important turning point, Michael then promoted a number of mainland Chinese to be part of his management team. In a single stroke, he broke the glass ceiling and sent a powerful signal to everyone in the organization that they had a future at TNT. As a direct result, staff morale improved and attrition dropped dramatically.

One of the first things I did for the sales team was to lower everyone's targets, simply to render them achievable. We rewrote the incentives program, and when we published it, people reacted mostly with disbelief. Everyone had become so accustomed to being treated badly and shown no respect by the foreigners, that they could hardly believe we would really make their lives easier and fairer.

So although we certainly worked very hard that first year, in many ways it was easy to improve. Essentially the only direction available to us was ‘up!’After we got a number of the ‘business basics’ aligned, the next challenge proved to be much more difficult.

In the market where we operated, our key competitors-DHL, Fedex, and UPS-were bigger with much stronger brand names. As the person responsible for marketing, I tried to convince the board that we needed to invest in our name recognition in China. Although they listened politely, they offered no additional investment. The previous marketing team had burned a lot of money on a very beautiful advertising campaign, and even though I could explain perfectly why the campaign failed (it was too clever for the audience), I convinced no one. Also, the board had always made the traditional, conservative assumption that, as a business-to-business company, TNT did not need to advertise as if we were a consumer brand. They failed to see why UPS would spend tens of millions of dollars to sponsor the Beijing Olympics. At that time, I disagreed with the board. But a few years later, I became convinced of a much better, more cost-effective way for us to compete and excel in China.

Following a number of conversations with Michael, we agreed that I would start exploring the idea of customer experience. I began discussing the concept internally and externally. Emma Cook from headquarters joined us for several months to help us develop our strategy. We thought a great way to begin would be to listen to what our customers were really experiencing. At that time, an annual customer satisfaction survey was administered globally, but its results played almost no role in any management discussion. The report contained so much information, much of it merely affirming what we already knew, that it quickly found its way into a bottom drawer.

When we first brainstormed with the management team about how ‘customer experience’ could become a key differentiator for TNT, we explored various scenarios to describe what the world would look like if we succeeded. One question we answered in a workshop was:‘If customer experience were a person, who would it be?’ Without hesitation, many team members responded, ‘Linda!’ I have since dubbed her, ‘Ms. Customer Experience.’

LISTENING TO CUSTOMERS

We came up with the idea of launching the customer experience theme during our 2008 conference. We organized annual conferences in Shanghai for the top 200 managers in China. Michael had started this practice, and these events became our yearly method of reconnecting the teams and re-setting their direction. Michael possessed a great sense for the fact that people mostly needed to attend these events to mentally ‘sign up' for another year with TNT. Therefore, he focused on creating a wonderful atmosphere and delivering outstanding content.

We began by filming a series of ‘candid camera' situations. The event company that helped us organize the conference pretended they were new customers of TNT, Fedex, DHL and UPS. They approached each company with a simple scenario: We have a parcel that needs to be delivered to London urgently. Can you help us?

We taped all the telephone conversations and secretly filmed every interaction with the sales people and the drivers who picked up the parcels. The results were baffling. The videos of this simple exercise pointed to one undeniable conclusion-our industry was almost impossible to do business with. None of the four companies managed to do well. Although almost everyone was polite-except for a UPS delivery man who barked at a receptionist, “I have no time to wait for you; UPS does not wait!”-the layers of bureaucracy and lack of professionalism made me cringe. Our salesman, certainly a nice and easy-going guy, showed up in jeans and remarked, ‘Sorry, it was my free day.” He simply handed the ‘customer' a price schedule, providing nothing at all to suggest we were any different from our competitors. These videos convinced me we had hit a ‘gold-mine;’ we definitely had a major opportunity to become the ‘easy to do business with' company.

We also listened to a number of random phone calls that had been taped at our call centers. One call turned into a shouting match between an English customer (his daughter was in the same school as mine-ouch!) and someone from our credit control team, the people chasing customers to pay their bills. The entire conversation made everyone cringe again; TNT's representative had shown so much aggression. We became even more embarrassed when we discovered that the employee in question had recently been recognized as ‘Employee of the Month'!

I don't think we could have imagined a more effective way to make an impact than those videos and taped conversations. If anyone remained skeptical about the importance of pleasing customers, everyone could at least agree it would be valuable not to upset them. Furthermore, we all became aware that we were rewarding people on how well they delivered on the key performance indicators (in the case of the credit controller: customers paying their bills), rather than evaluating the methods they used to achieve those goals.

A FRAMEWORK FOR CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE

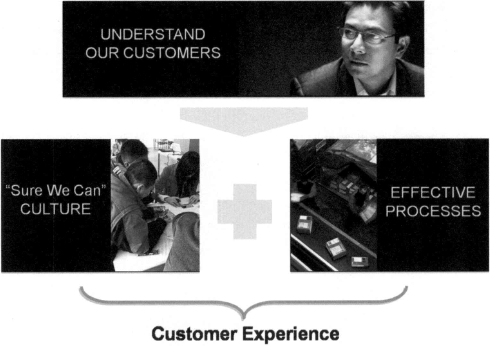

We then presented a simple, conceptual model that continued to function as our framework in the years that followed:

This framework illustrated the importance of starting to really listen to our customers. Their input would set the priorities for the two critical building blocks: A great culture, and customer-friendly processes. With this framework, we already recognized the need to design these two components of our strategy: people and processes.

Although I believe we built the right framework, many details were still missing. We had yet to provide a clear roadmap to implement the framework, and more importantly, the customer experience journey was not accepted as the central journey. As the Marketing and Sales Director, I realized such limitations meant that the organization understood our framework mostly as my team's initiative. Although Michael did strongly endorse our direction, in his presentations he positioned our model as merely one of the things we were doing. We had not yet discovered how pertinent, meaningful, and all-encompassing this framework could be.

Furthermore, although we had strategic priorities (mainly, become the leader from China to Europe) and we had an idea for a differentiating platform (customer experience), we still lacked a strong vision. We did not yet possess a compelling, overarching image of what we wanted to become.

As a result, in the months following that conference, not much changed. We stayed very busy running our business, but I had difficulty getting customer experience on management's agenda. Neither operations nor the finance community were really interested. Michael and I realized that we really needed to reach the core of what we were trying to achieve. But I couldn't convince him that a great deal more of what we were accomplishing needed to revolve around customer experience. I guess in his‘heart of hearts,’ he still struggled to understand how filling up the airplanes, managing the P&L and all the other day-to-day activities fit within the concept of customer experience. We still lacked a clear mission.

Even though relevant textbooks claim that everything starts with a mission, we did not arrive at that conclusion until after a year and a half or so after our arrival. But because we had been exploring several issues and topics relevant to a mission, finally choosing the right one was not very difficult. After brainstorming with the management team, we came up with these simple notions:

A great company to do business with

and

A great company to work for

After we reached consensus, Michael and I agreed that these two components of our mission essentially mirrored the two pillars of our Customer Experience strategy. From then on, we ‘conducted from the same orchestral arrangement' -Customer Experience was the ‘umbrella' theme covering everything else.

During this critical formative process, we met the founders of Reya Group, Jesse Price and Jeremiah Lee. They had just launched their consulting company with a strong focus on organizational design. Jeremiah and Jesse (with a few of their colleagues) provided a tremendous boost to our organizational transformation, becoming our ‘thought partners;’more personally, we also became great friends.

Some of the first insights I learned from Reya came from a case study of Enterprise Rent-a-car in the US. This company had rebuilt its business on a customer experience platform. It took them many years to accomplish this, mainly because for the first few years they did not make it their core program. Once they embraced customer experience as their fundamental value, carefully aligning all HR processes to achieve that (including remuneration, incentives and career progression), and really began empowering their staff to lead from the frontline (close to their customers), their business exploded.

I gained a lot of wisdom from Enterprise's remarkable success, and the whole idea for a ‘customer-experience-centric' enterprise started to crystallize in my mind. If we nurtured the right culture, if we empowered everyone to lead within their spheres of influence, the organization would truly come alive, and we would deliver great customer experiences from the frontline. Until this epiphany, I had assumed that all ‘big ideas' had to come from us, from leadership. Enterprises experience demonstrated that we simply needed to provide clarity about what and who we wanted to be and build a supportive system-and our people would take care of the rest.

These were revolutionary ideas to a transportation company, where everyone mostly focuses on standardization, efficiency and limiting flexibility. I started to promote basically the opposite set of values-context, effectiveness and adaptability-and from then on, it proved difficult to align what we were doing with what headquarters was doing. Their idea of ‘customer experience' was to teach everyone exactly how to do things in the friendliest way possible. Our idea was to create customer friendly processes, but then give people as much freedom as possible to create their own solutions to problems. We brought empowerment to China-at odds with the company culture and the national culture.

'SURE WE CAN' CULTURE

I have always intuitively felt we had to try to create a great culture, but I never had the theoretical framework or any practical tools to accomplish this. Reya-eventhough they had not developed all the tools we would later use-provided both. Although difficult to interest the management team members in ‘managing' our culture, they all eagerly engaged in a workshop exploring our current culture and how we wanted to change it. As you might imagine, we had a lively debate! We spent a whole day discussing aspects of our culture like the ‘drive to achieve' and the desire to ‘keep things under control.' This notion of ‘control' proved especially contentious. Most agreed that the company was much too controlling and imposed too many rules and procedures. But many were afraid to create chaos by loosening the grip management had on the company through its numerous policies. To provide just one example-we had a raucous debate about TNT's strict controls on employees' use of the Internet; many sites like chat rooms and even Yahoo were blocked because of abuse and other bad experiences in the past. I argued that we could trust our employees if they were really engaged in their own and TNT's success, but such reasoning had little influence at the time. We did agree to remain focused on achievement yet we also included more personal, social goals. Regarding our emphasis on ‘control', we decided we needed more effective control with less burdensome bureaucracy.

SIX CORE VALUES

We had far less trouble determining the values we would uphold than we did reaching consensus about our culture. While TNT's senior leaders officially disseminated a number of core values, few people knew these values, and they certainly enjoyed very little real meaning. Nonetheless, in our discussions, we remained in as close agreement with those values as possible.

Reya Group suggested a really interesting idea: the management team should not act alone in developing our values; we needed to include ideas from the field through a series of workshops. They introduced the notion that by including lots of people in setting our direction, we would achieve greater buy-in-even if we didn't follow all the suggestions. For the first time, we really put that concept into practice by organizing a number of workshops in the field very similar to the one that we went through with the management team. This integration of ‘top-down' and ‘bottom-up' brainstorming became a crucial component of everything else we accomplished.

Interestingly, when we compared the values from our management team with those provided by our people in various cities, they were quite similar. We had prioritized four of the five core values they had identified. We settled on the following six core values:

Teamwork

Trust

Satisfying customers every time

Ownership

Challenge and improve all we do

Honesty

Michael and I insisted on only one value on this list that had not been emphasized previously-ownership. This value certainly ranks very low within most Chinese people's personal values. The reason for this is that taking ownership means taking risk. Taking risk means standing out from the crowd and potentially being wrong. Both aspects are culturally not very acceptable in China. Yet Michael and I believed that we needed to push this value if we wanted everyone to take an active role in creating a great customer experience. We also knew that in some ways corporate culture can trump national culture, so we included it on the list.

I was very happy to see that everyone embraced the value of trust and wanted to see it increase. We all knew that trust can be very difficult to find and even harder to create, but at least we agreed that higher levels of trust would help us achieve success.

Choosing our six core values directed what we wanted our culture to become. These values and the culture we wished to build from them had not yet captured very many hearts or minds, as they soon would, but at least we had begun our journey.

Toward the end of 2008, the team from headquarters launched an initiative to introduce a new global slogan for TNT. We in China also became involved, finding this to be a fun exercise. The results from this discovery process showed that people around the globe pretty much agreed on what TNT did well. Consequently, the team in Amsterdam came up with the catchy phrase,“Sure we can” mostly to reflect our ‘can-do' mentality. We never garnered much praise for the slogan outside the company (admittedly, it was not very distinctive or original, and Obama had just run for the US presidency with the slogan, ‘Yes we can), but internally, the tagline worked very well.

To link with this initiative and to indicate to the teams in China that we wanted to align with the direction from headquarters, we referred to our values and cultural initiatives as ‘creating a 'Sure We Can ‘Culture.' That effort worked extremely well. ‘Sure We Can' soon began appearing as a line in many emails and presentations, a positive encouragement reflecting the values we were trying to engrain.

One missing key to ensure success remained-we had to find a way to make these six core values really ‘come alive' to inspire our employees. I will describe that process in the following chapters on Andrew Yang and Max Sun.

PROCESSES

I will devote little time in this book to our efforts to make our processes more customer-friendly. This was (and is) not an easy thing to do, certainly not for the leaders of one country's operations within a globally networked enterprise headquartered elsewhere, leaving limited freedom to make structural changes. However, we did discover that many difficulties could be traced to poorly run implementations of processes that in themselves were fine. We launched many initiatives to streamline such implementations, but primarily, we gradually empowered employees to generate their own ideas for improvement, informed by local conditions, and then when and where appropriate, we rolled their ideas out across the country.

Headquarters suggested we train people in Six Sigma/Lean, a structured approach to management practice that uses systematic, quantitative techniques for process improvements. Although common in industrial settings, Six Sigma/Lean is rare within service companies. At first, we struggled to implement these tools. Finally in 2010, my management team decided we should ‘lead from the front.' We all embarked on becoming ‘greenbelts,’the title given to those trained and certified to lead process improvement projects. We soon discovered just how difficult these tools would be to implement in a service environment. And although I said nothing, I realized almost immediately that Six Sigma was too rigid and complex to be very suitable for contributing to the company we were building. But on balance, our experience with Six Sigma showed people that we could improve our processes. Indeed, within three years, we as a company became easier to do business with-which is not to say that we were really easy to do business with when I left TNT in early 2011.

MEASURING CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

The first year we established our core values to strengthen our culture, we focused on achieving the mandates in the top box of our framework (‘Understanding our Customers'). But to truly understand our customers, we needed to collect feedback from them systematically and then use that information to make necessary improvements.

We began by attempting to analyze the results of the annual survey already sent to all our customers from corporate headquarters. Although the processes for administering, interpreting and communicating about this survey were poor, the survey itself was actually good. Reya Group explained that the questionnaire was clearly developed by knowledgeable, competent researchers, but we just did not have the in-house tools or focus to translate the information into easily digested implications that could be acted on by management.

In addition to improved translation and interpretation of this annual survey, we wanted more frequent feedback than just once a year; we also needed a much higher response rate than the low percentage we often observed in China. We decided to conduct a short, monthly survey of some of our recent customers; we would run this supplemental survey for 11 months, but then once a year, with the rest of the company, we would participate in the long survey.

The short survey consisted of eight questions that focused on each of the important elements of our service. One final question asked,“Would you recommend TNT to others?” This is the ‘killer question' in any customer satisfaction survey-the question you must ask if you can only ask one. Results from this question allowed us to determine how important customers rated us on the various other elements (for technical readers, the ‘derived importance'). We could then calculate a customer satisfaction score between 0 and 100. That is what I needed-a simple way of communicating how satisfied our clients were with us and if we were improving.

We worked backward from the results of the last annual survey to measure this overall customer satisfaction score: 64. We then sent a short test survey to a limited group of customers, achieving a good response rate. This yielded a satisfaction measure of 65. Bingo! We had our baseline.

THE LACK OF A MANUAL

It was easy to explain to our employees that we launched these surveys to learn what our customers were thinking. It was more difficult to overcome the objection that the survey did not provide many details about where we should focus to improve. Of course, this challenge contained elements of truth: if customers merely indicate they are unhappy with their value for the money, this does not reveal exactly what they want improved. Additionally, these results seemed to support the contention of people who always simply pushed for lower prices.

I explained repeatedly that no detailed ‘instruction manual' existed for improving the Customer Experience. Accepting that step-by-step operational procedures to deliver improvements were non-existent represented a difficult conceptual change for most of our leaders. Trading objective measures of performance, easily expressible in terms of financial impact, for a seemingly unpredictable, uncontrollable measure challenged many of their foundational beliefs about how to ensure successful business operations. Our measure of service yielded a rigorous, quantitative result (a score from 0 to I00), but many argued that we merely measured the poorly understood, subjective view of customers. Our managers preferred to focus on ‘hard' operational data, like transit times for shipments or damage ratios (aspects of performance we did in fact measure), but I continued to believe that what customers really experienced, though intangible by comparison, remained of primary importance for guaranteeing success. To illustrate, even receiving a damaged shipment can be a positive experience for a customer, if we proactively communicated about the damage and offered to compensate them.

To elicit more details from the survey, we included an open question, giving respondents the chance to provide more comprehensive feedback. We also trained all local management teams in conducting structured interviews with customers, allowing more opportunities to interact with customers and yielding more practical information about what was really important to them. This contention, "We want to know exactly what to do.’continued to drive discussion. It proved almost impossible for some to accept my claim that customers often did not even know themselves, exactly what they wanted changed. I used the example of a restaurant with a ‘bad atmosphere' because people at the next table are loud or not enjoying themselves. While patrons may not even consciously notice, this will still impact their overall impression of that restaurant. Moreover, the more I read about behavioral economics, especially the amazing work of Dan Ariely, the more I became convinced that the specific details so sought-after by some of my managers did not matter as much as a focus on the customer experience itself, and the empowerment of employees to improve our service that would naturally accompany such a focus.

CARING FOR THE UNLOVED

That notion that the focus on customer service itself was the key to success proved to be correct. In the first year after we launched the Customer Satisfaction Index (CSI) we did very little structural work on process improvement, yet our score improved month by month. After one year, from the end of 2008 to the end of 2009, we moved from 65 to 75 on average. It was our focus, our communication, and the mere fact that we were engaging with customers that made the difference. Our customers loved the attention.

Related to that observation, an extraordinary insight occurred to us: our customers loved our attention because they were largely unloved inside their own companies. Most of the people in our client companies were logistics managers. Seldom represented among the most senior organizational leaders, often they hold positions that go unnoticed-until something goes wrong. So when we as a company really committed to giving them personal care and attention, they loved it. I discovered this first hand when we invited 100 managers for a two-day conference, which included some knowledge/content as well as several fun activities. I never expected the turn-out: 80 of them showed up! Suddenly, I realized the Board had been right to refuse to spend large sums of money on marketing. All we needed to do was build relationships with the people in our customers' companies. I also made a mental note to discard the classifiers, ‘business-to-business' and ‘business-to-consumer.' The only meaningful category for any enterprise is ‘business-to-people!'

Our first 10 points of improving the CSI-from 65 to 75-represented the ‘gift’ of getting on the right track. However, I realized that improving from 75 to 85 would be much more difficult.

85

By the time I became fully convinced that Customer Experience was the thing to do, I learned that customers who really love what you do for them become your advocates. Based on my reading and estimates from Reya Group, we needed to score really high (CSI of 85 out of 100) average satisfaction for this transition to happen. In every presentation, we began using 85 as the goal to reach within three years.

Publishing the CSI results by region and depot every quarter created strong internal competition. The Chinese are raised to be really competitive-not so strange when considering the large number of competitors. An advantage of this competition was the fact that depots took their CSI results seriously. A disadvantage was that some of their results were not directly comparable. Ideally, the focus should have been on improvement over time; depots should really have compared their results with their own previous scores, not with other depots.

INCLUDING CUSTOMER SATISFACTION RESULTS IN OUR REWARD SYSTEM

Just as with Enterprise Rent-a-car's experience, old patterns of behavior among our employees did not really change dramatically until we incorporated the CSI into our performance and reward systems. Because we understood the importance of this contingency from the start, we communicated well in advance that we would soon make CSI the most important factor in bonus calculations. We took nearly a year from the first CSI results to link these results to bonuses, partly so people could get used to them, and partly because we wanted to see if our CSI measure would give relatively stable results.

In the middle of 2008, Michael was promoted to lead the North Asia region. I was appointed as General Manager of TNT Express in China (Hong Kong and Taiwan were added later). Initially only the regional general managers reported to me, but a few months later, we added functional directors to the team. This structural alignment helped me move the CSI initiative from its perceived ‘marketing and sales' focus to the overall company theme. Without this change, I don't think we would have had the functional support or the ‘guts' to really make the CSI the core measurement for bonuses. I had long discussions with my new management team considering whether we were ready to ‘take the plunge.’ People were nervous that field members would not understand it, that they would miss the connection between their own work and their bonus; but mostly, the objections centered on the lack of a clear path for delivering a better customer experience.

The ‘believers’ among us ‘pushed back,’ explaining that financial results (then the prevailing measure for bonuses) can also be highly subjective (even the rules of accounting policy allow for some interpretation), and EBIT can be very disconnected from people's individual contributions.

The proposal we settled on called for the CSI quarterly bonus to represent 50% of the total bonus available. We chose a quarterly bonus because people respond more reliably to relatively short-term results. We also agreed that for the first year, we wouldn't set overly aggressive sales targets, and we kept the option of adjusting them every quarter. These considerations would create and maintain confidence among the staff (and my own team!).

Every depot and region was given the task of achieving a CSI score of 85 within three years. Therefore, low-scoring depots had to increase their scores faster than

Linda Pan-building a company based on the experience of the customer better-performing ones. Employees of depots scoring over 85 would always receive full bonuses plus an extra incentive.

The stiffest resistance came from the HR team. Helena, our HR Director, certainly agreed to the plan, but members of her team tried really hard to obstruct implementation, in spite of the management team's unanimous support for our final proposal. I finally ‘played my power card' to resolve the impasse; I told them this was the decision, and they needed to execute the program.

Once the CSI results began accumulating and large groups of employees were earning their bonuses (without much adjustment to the CSI targets we set; we made only a few exceptions), we started to see a genuine shift in people's attention. Indeed everyone became focused on trying to find new ways to improve our customers' perception of our service and service attitudes. I will describe these results in more detail in the chapter on Yu Bo.

A NEW TEAM MISSION

Once we installed my new management team at the end of 2008, we started to switch gears and drill even deeper into these issues. We put Customer Experience at the heart of everything-even appointing a director to oversee the plans and progress across the various functions and regions - and we started to critically evaluate how we could best achieve our mission for TNT. We devoted a number of team sessions to delineating the culture we hoped to build, and also to how we as a team wanted to work together. We decided to create our own team mission to encourage excellence even above and beyond what the company wanted to achieve. We consolidated many ideas supporting our desire to create a really exciting place to work, to excel with our business, and even to contribute to China’s economic development. We agreed on the following mission statement:

Touching People

Moving Goods

Connecting China to the World

And from then on, that is precisely what we set out to do.

(selected from In China We Trust by Iman·Stratenus, published by China Intercontinental Press in 2018)