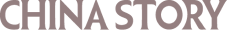

Angelina Wan's nickname as a child was‘Dao Dan', 'bomb', partly because her father was in the bomb production industry, but mostly because of her temperament. I would instead compare her to fireworks, but of the beautiful sort with bright colors and lots of surprises. We hired Angelina soon after I arrived in China, and to this day, she remains the most open, honest, outspoken, independent, creative, bubbly and fun-loving Chinese person I have ever met. She is honest to the degree that she cannot keep her mouth shut even if it were much wiser for her to do so. She is absolutely fearless -- but very sensitive at the same time.

Even though Angelina did not initially report to me, she communicating with me on many subjects from the very first day she joined. She would tell me about things that frustrated her, about people she liked or disliked, about ideas she had. She needed no encouragement to take initiative; rather, I had to soften her enthusiasm many times to make sure she did not create too much resistance to change among other staff members.

Angelina thinks so fast and so creatively, that during her first two years with TNT, I often had a really difficult time understanding what she was talking about. A‘thinker-talker,' she frequently included many apparently irrelevant details while addressing pertinent issues. But from her very first day on the job, her employees loved her. Angelina soon became the darling of our worldwide Customer Service Director, Chris Goossens, a wonderful woman from Belgium who became the biggest sponsor at corporate headquarters for the organizational transformation to which we aspired.

Running a call-center anywhere is an extremely difficult task. Staff members work very hard on the phone, addressing complaints and dealing with inevitable stress. Often they endure long days and nights. Employee turnover is usually high, in some places over 100% per year. With these daunting prospects, Angelina faced the task of bringing some 30 small call centers (one in each depot) together to form three large regional call centers, each with 60 to 100 people. Within three years, based purely on her enormous energy and talent to engage -- or rather, deeply touch -- people, she had created three call centers that became some of the best in all of China; staff turnover fell well below 15%. Probably the biggest factor in TNT China becoming a best-in-class service delivery organization rested on the consistently high level of customer experience provided by our call centers. The pictures from her team-building activities looked more like they were taken by groups of best friends! This example provides but one of many possible‘behind-the-scenes' glimpses to illustrate Angelina's contagious influence.

In all honesty, over the years, I personally had very little to do with the success Angelina created. I just watched and enjoyed the show. I let her get on with her plans (and again, many times I struggled to understand what she was saying due to her talking speed!). But she was implementing the corporate standards necessary to run a call centre with great diligence, and so I really never had to get deeply involved.

Born in Hangzhou in 1976, Angelina grew up in Nanchang, the capital of Jiangxi province. She stood out from the crowd from a very early age, encouraged by her father to be unique and resist conformity. As an engineer working in an arms factory, her father was a staunch supporter of everything the government did. Yet he allowed Angelina to be a‘rebel' (not in a political sense) and gave her pocket money when she began second grade. Among her friends, Angelina was the only child to enjoy such trust, and she always bought gifts for them. She also habitually gave her shoes and shoelaces to poor children in her class, who would get beaten at home if they had no shoelaces. If she got beaten or scolded for her generosity, Angelina simply did not care. Once her father scolded her (he would not beat her) when her shoelaces again went missing, but this time the culprits were rats in the house. Angelina remembers crying when her father unexpectedly apologized to his young daughter. Such tender behavior was unheard of then.

Angelina always had boyfriends during school and college, and she managed to remain the center of attention among her many friends. Due to her impulsive nature, she usually got in trouble with her teachers; once she was even expelled. She missed entering law school because she forgot to attend the day of the exam. In her own words, Angelina‘just goes with the flow.’She ended up studying economics and after graduation went to Shenzhen to ‘try her luck.’ First, she worked in an advertising company as an copywriter. But because she‘wanted to see the other side of her feet.’she moved to Canada to complete an MBA. In Ottawa she again developed a wonderful social life, anchoring the orbits of a large group of friends. While pursuing her studies in marketing and‘high-tech management”she had almost no money, slept in a sleeping bag and worked illegally in a supermarket. Not surprisingly, she occasionally argued with her Canadian professors, mostly over grades that in her opinion were too low. She also argued with other students about Chinese politics.

Actually, I learned an important lesson from Angelina about Chinese politics. She has strong opinions about the politics in China and remains very open to sharing her views. But she is also very patriotic and therefore does not like foreigners to point out China’s problems. She told me once that China’s challenges are ‘not ours to worry about.' She may be the only person to ever tell me this so explicitly, but I sense most Chinese deeply share her perspective. Similarly, as a Dutch person I also love to argue with other Dutch citizens about our politics, but I tend to be much more defensive about such topics with foreigners. My own personal perspective on Dutch politics thus reminds me that I am an observer in China. The Chinese people are largely not interested in my views on their politics. Accepting my ‘observer role' regarding Chinese political discourse has offered a healthy opportunity for personal growth.

During her two years in Canada, Angelina noticed that many Chinese manage to find only low-skilled jobs, such as working in restaurants, so she decided to return to China. However, this decision also presented many challenges. Even with advertising experience and holding a marketing degree from Canada, Angelina still required six months of endlessly sending out hundreds of applications every day to find a job she really wanted. She became the Customer Service Director for China Unicom in Shenzhen, where she worked very long days managing a team of 120 employees. During this stint at China Unicom, she made many friends and a few enemies. Those enemies relentlessly pursued her, leading to her resigning one day in front of all her supporters -- an event she still only recounts with tears. Angelina says this episode taught her to remain more‘low profile,’ but I must admit I did not see much‘low profile' behavior from her after she joined my team.

Angelina then spent several successful years with Dell in Xiamen, where we discovered she had a great reputation. Although at the time Dell's corporate profile far exceeded TNT's, she still accepted our offer, because she had become ‘bored with Dell's data mania.’Dell tried many inducements to entice her back, and for the first month, Angelina was tempted to return. But thankfully she followed her intuition and stayed with us.

Angelina offered this explanation of her difficult transition from Dell to TNT: “In an American company, you get a set of keys and a manual, and they put you in front of a number of locked doors. If you follow the manual, then you open the doors one by one. In a European company, the doors are all open, but it is pitch dark. And so you have to go into each room and try to find the light switch. If you can't find one, you just try the next room.”

In spite of these initial challenges, Angelina eventually came to embody our positive culture. She shared with me once that TNT is a place where ‘she feels she can fly.' She loves the tolerant and positive atmosphere. I often had to remind her that she had helped create that environment. Although many employees had to forge new connections and make important changes to adjust to the culture we were creating,

Angelina was probably the one person on my team the new culture fit most naturally,and she therefore became a skilled mentor to many people.

EXCITEMENT IN A CALL CENTER?

With someone like Angelina on the management team, it was easy to try new things. She herself proved to be an endless source of new ideas, mostly on the topic of how to further engage her teams. As mentioned previously, managing call centers represents a daunting challenge. People who pick up the phone more than 200 times a day for a living are difficult to keep engaged. Young graduates often start their careers in China as call center staff, simply to gain experience that will then allow them to find a ‘good job.' With such high, intentional turnover, it is difficult for leaders to encourage their staff sufficiently so that they provide decent, quality service. Most call centers therefore impose very strict call ‘scripts' to which the staff must adhere.

Angelina maintained a contrary view. She fervently believed it was entirely possible to create a great working environment in a call center, to get people really engaged in what they were doing and especially with the people they worked with. By focusing on creating a great working environment, she believed people would stay longer, perhaps even embrace the job as their career, and deliver excellent customer experiences.

Every time Angelina would update the management team on progress in the call centers, a large part of the presentation would contain pictures of team dinners, team building activities, and internal competitions of all varieties. The entrance to each call center featured what she called a ‘smiley wall' -- pictures of staff members who worked there. She allowed people to personalize their work spaces, and most importantly, she spent enormous amounts of time talking to these critical, frontline staff. She knew people by name and kept track of their career development. Almost all promotions were internal.

At some point the corporate head office suggested that the Hong Kong call center(with their much more expensive staff in a much more expensive building) could perhaps transfer some of their work to the Guangzhou call center. The Hong Kong team stoutly resisted this transition, partly of course to keep their jobs in Hong Kong, but also because they genuinely believed that their years of experience made their service superior to the ‘group of young enthusiasts on the mainland.' We decided initially to transfer only a small part of the work and then measure the service by customer surveys and follow-up calls. From the beginning, the Guangzhou team outperformed the Hong Kong team by a mile! Although using the same scripts and procedures and with fewer years of experience, their high engagement levels simply translated into high levels of customer satisfaction. The Hong Kong customers began reporting an improvement in the service levels from TNT without realizing they were now being served from Guangzhou. It took the Hong Kong team quite some time to come to terms with these results.

Angelina and her teams enrolled in a few external competitions and were twice voted ‘best call center in China' -- one year with the South Region call center and the next year with the East Region call center. These decisions to compete were always deliberate -- Angelina only enrolled a call center in competitions if she was convinced they could win.

TRYING NEW THINGS

The story of what Angelina accomplished in TNT's call centers is exemplary for many other reasons as well. Once we started to see the teams feel more confident and engaged and the business improve, everyone became a lot more willing to challenge assumptions and try new approaches. Tom Peters, in his excellent book, ‘The little big things' (Did he write that book just for us?) claimed, ‘Whoever tries the most stuff, wins.' That became a mantra for me. Let me give you a few examples of atypical directions we ventured into.

THE MAGIC BOX

Because the launch of Customer Experience was our main mission, we wanted to find a way to collect and spread great ideas from the field. When we started talking about a ‘suggestion box,’ many expressed skepticism. ‘Suggestion schemes are doomed to fail,’ captured the general opinion. Yet a few of us believed we should still try to see if we could make suggestions work. Yu Bo's work in Dalian was a strong motivator for us. We first thoroughly evaluated why most schemes fail. We concluded such failures must happen because people don't feel their suggestions have any impact -- they don't receive feedback. Many on my team argued that people needed to be rewarded, preferably financially, but I didn't accept that argument. Many incentive schemes attach financial rewards but still generate few ideas.

We all believed that many great ideas existed in the field; to leverage this potential, we designed a process that would ensure there was feedback and a real chance for good ideas to be implemented. Certainly the collective intelligence among our field members must exceed that within the management team alone.

The process we designed featured a ‘standing committee' consisting of representatives from various levels and departments and always chaired by the Customer Experience Director. This entire committee would review every suggestion, so the finance department representative would also evaluate HR initiatives, etc. Fully empowered to decide whether an idea was worthwhile, this committee passed approved suggestions to the relevant department, region or depot for implementation. If a suggestion would change company policy, it would require a decision from the China Management Team.

This standing committee met regularly, and all suggestions were made public and received feedback. Furthermore, the composition of the team changed each year.

I will not claim the Magic Box worked perfectly, but we did get on average about 40 suggestions per month for two years. Half these were implemented. Some who submitted suggestions complained that the feedback was not elaborate enough. I personally would criticize the committee's incessant attempts to compartmentalize for efficiency (i.e., the finance representative would address finance-related suggestions).I thought (and still think) it crucial that the committee consider each suggestion collectively, but such an interdepartmental view remained somewhat alien to my Chinese team members; still, we improved with time.

I should mention one other important advantage represented by the Magic Box-- it sent a strong signal that everyone was empowered to think and had a chance to make an impact. I was positively impressed by the fact that suggestions came from all levels of the organization. Later, while reading books on psychology, I learned that giving people responsibility is a very powerful way to engage them. Even giving people a small level of responsibility within the ‘grand scheme of things' provides them with some choice, some control over how they accomplish their work. Such a sense of personal latitude influences employees' work attitudes. Incidentally, this explains exactly why subordinates hate micromanagement so much: micromanagers deny choice and responsibility, and by so doing they unknowingly communicate threat (for more on this subject, see David Rock's insightful book, ‘The Brain at Work').

We received several great ‘small' suggestions, like from a truck driver who suggested we place the TNT logo on his uniform on the left instead of the right arm,so that people could see it while he was driving. He wanted to be a marketer for our company. Talk about impact!

In contrast, we did not receive many‘big' suggestions. People seemed to retain a reticence that‘We really couldn't change the big stuff.' I sensed we needed to communicate in a more powerful way that we were willing to ‘take on anything.' So in 2010 we held a Spring Cleanup.

Inspiration from Kindergarten

I actually got the term, ‘Magic Box' from my daughters' kindergarten. We only borrowed the name and its basic concept of a box that can create magic. In kindergarten, the box held some mysterious object the children got to learn about. This kindergarten, the Julia Gabriel Center of Learning, was a good source of inspiration. They illustrate and practice positive psychology every day. It is really amazing to see how they can create such a lively, yet perfectly ordered community of learning and positive development. They only use gentle correction, and their approach has taught me a lot about how to raise my kids and how to deal with my colleagues. I now live by the mantra that with some adaptation, if it works for three-year-olds, it will work for adults as well.

SPRING CLEANUP

In addition to strengthening the impression of the impact any employee could have, I wanted to send a strong, clear signal to our teams implementing Six Sigma process improvement initiatives that they needed to be bolder. These Six Sigma teams were spending a lot of time talking about organizational structure, training people, creating manuals. I calculated that at their current pace, it would take years before we really began grappling with the big issues of slow and inefficient processes.

The Spring Cleanup concept was simple: everyone in the China Management Team would speak with their team members and bring the five most frustrating processes or procedures to a two-day meeting. In those two days, we would‘clean up' those practices that we as a team agreed we didn't need or that could be changed.

For this two-day meeting, we locked ourselves in a big meeting room in a hotel across from the office. We made decisions on 43 processes and procedures. Some discarded procedures took a while to really end, but many were ‘thrown out the window' right then and there! It felt liberating to actually do something really useful -- removing barriers so that employees could accomplish their tasks, hassle-free.

Here is one example of a process we changed: apparently, I had been signing a form to allow the use of the official company chop (the stamp needed in China for any document to be official) and then sending it to the legal department. Even those contracts that bore my signature would only be chopped by the legal team if they also had a form signed by me that allowed the use of the chop. I asked the legal team what they thought the chances were of me not allowing them to use the chop on a contract that I had already signed. They looked puzzled, yet agreed that the chances were slim. By discarding this requirement, we saved a number of people quite a lot of time, because travel, too, often delayed the signing of documents.

Our Spring Cleanup uncovered many other inefficiencies, so I split my time for the entire two days between frustration and joy -- frustration when we discovered yet another inefficiency, and joy when we got rid of it. Afterward, I felt we had communicated the right message to the field: we were serious about ‘cleaning up!'

AWARDS

Giving awards for good behavior defined another successful technique my daughters' kindergarten used. Similarly, to begin each management team meeting, I bestowed a few awards for exemplary behavior. These awards consisted of simple certificates or plaques that read something like, “You, Andrew, are fantastic for having developed your team so well that three people have been promoted in the last month.”The language “You, [name], are fantastic for...”came directly from the awards that the kindergarten hands out every Friday to a few children in each class. The pride on the face of the kids compared very well to that of my team members, many of whom were older than I am. Many of these awards would end up on walls near their desks, just like my kids hung their awards in their bedroom or in our kitchen.

A second benefit of beginning every meeting by handing out awards, which I only realized later, was that these small celebrations set a positive tone. It was difficult to sink into a collectively negative mood after we cheered on the award winners. Indeed, while certainly some meetings were better than others, a positive mood infused almost all of them.

CONFERENCES

TNT loves to organize conferences! Every region, country or function organizes at least annual conferences, bringing scattered people together. Most of these conferences occur in rooms equipped with a screen adorned throughout the day with a long list of presentations trumpeting the direction of the company, and the plans and themes for the next year. Team-building activities and some fun during dinner often follow these presentations. Much of the entertainment tends to be outsourced.

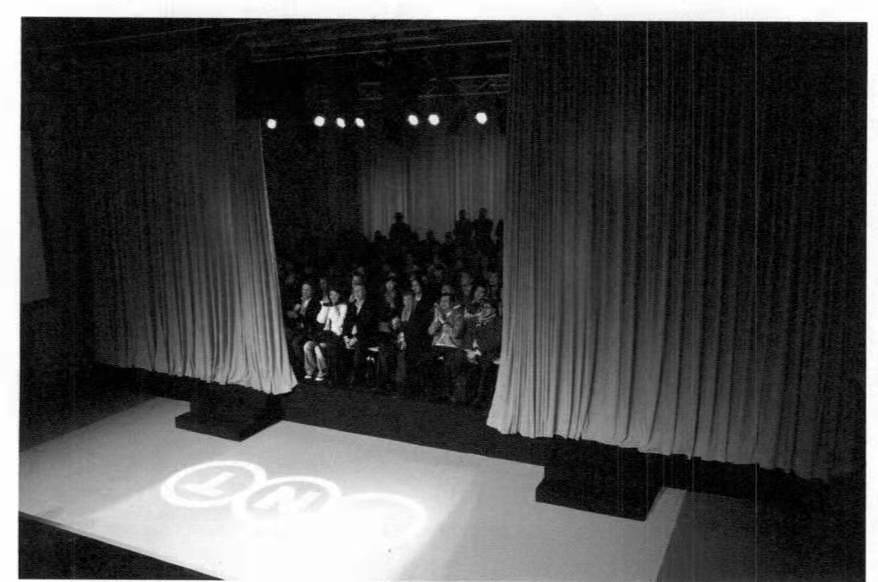

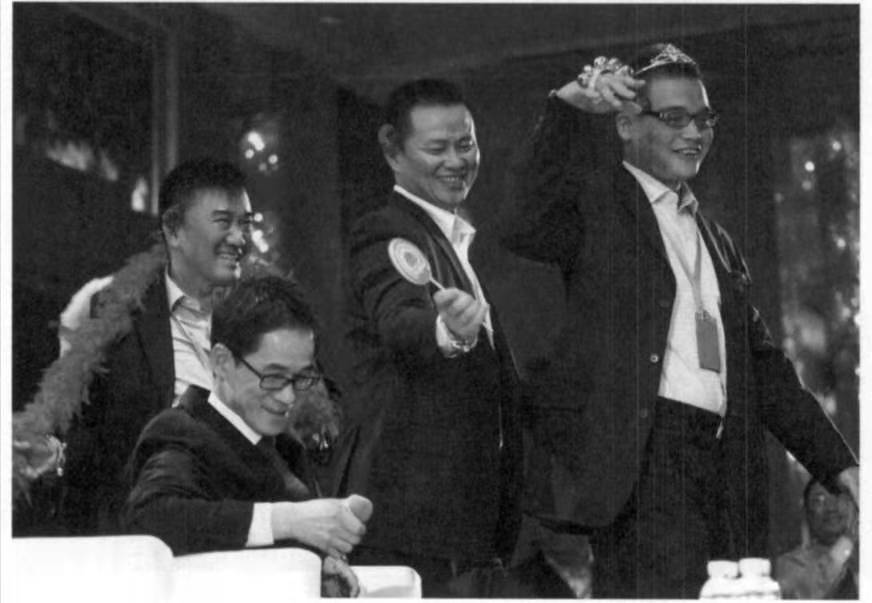

In China we held our annual conference in January. From 2007 to 2011, instead of using the traditional format, we organized much more interactive conferences. The key element in this shift was that we involved a large group of our own people to organize the event. A few months before the conference, we convened a group of people from various parts of the organization (I handpicked a few ‘connectors' from the informal network), and we brainstormed about new activities we could include. That team not only coordinated the preparation of the conferences, but remained engaged throughout the events. Two people acted as hosts, a job requiring days of rehearsal. At the end of each conference, the list of people to thank became longer each year.

The consistent, central theme was Customer Experience, a major contrast to most other conferences that always presented a new theme. The fact that we featured Customer Experience for several years in a row helped galvanize the message that this was our long-term mission.

We discovered our people loved performing on stage, so to communicate many important messages for transforming the company, we either asked some people to perform‘role plays' on stage, or we split the groups into small teams to create and perform small plays, with stage props and all. It was never difficult to persuade the entire group of 250 people to act hilariously in front of everyone else, and humor helped people understand and embrace change.

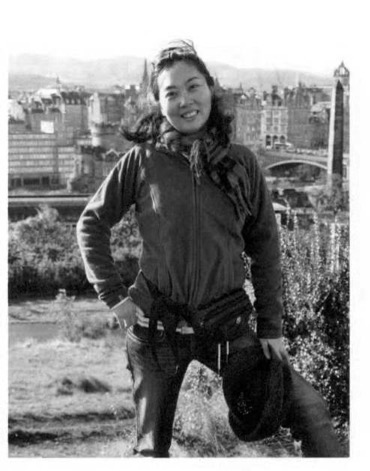

We spared no effort to align conference venues with this interactive format. One year we created a huge stage on which we placed 250 chairs. We closed the curtains and let people enter the conference room from behind, allowing them to find their seats. Everyone sat down expecting the curtains to be raised, exposing a stage in front of them. Instead, they saw an almost empty theater hall, with only a few seats filled by the management team. We began the conference by explaining that for this event, they would be the ones on stage. It worked beautifully.

Our own employees provided all the entertainment at these conferences, and this became a tradition for other events. We discovered so many actors, singers and dancers among our 3000 staff that we never again invited professional performers for any event.

The Audience on stage

The management team explains that they are the audience

Our people were always very excited about having the chance to show off their talents. Audiences also remained much more engaged watching their own colleagues perform.

I did my part to try and make my performances in these conferences worthwhile for the audience as well. The year we launched the ‘Magic Box,’ I came on stage as a magician. Another year I dressed up as a mountaineer with full equipment to underline the message that climbing the mountain of ‘Customer Experience' was no easy walk, but at least we were all clear on which peak to tackle.

We always used Auditoire, an event company, to help us with the practicalities of the conference. Every year Auditoire enjoyed working with our teams. One year, while building a small museum to highlight all the excellent Customer Experience initiatives from the field, I overheard them questioning among themselves why their company never organized anything like this for them.

These conferences thus became an important tool to engage our most senior people in China. Staff turnover in this group of 250 was negligible, and being admitted into the conference was a major source of pride.

Role plays and funny skits

BRINGING EMOTIONS INTO THE CONVERSATION

One of the most challenging goals I embarked on was an effort to bring people closer together by creating a work environment where showing emotions would be accepted. This goal initially came from the insight from the culture assessment of a serious disconnect between the value profiles of the management teams and the field's perceptions of those values. I therefore concluded that if we behaved more authentically, rather than merely playing certain roles, we would be much more valued and also become more effective leaders.

In 2010, an additional ingredient in our transformation process came from my gradually increasing exploration of the field of psychology and its implications for organizational development. An area of particular focus was the relatively new field of positive psychology, which studies what makes people happy, successful, optimistic, etc. For much of its history, psychology has mostly focused on studying what is wrong with people, not how they succeed. This shift in emphasis seeks answers to such questions as, where does the notion of fairness come from? What causes me to feel part of the group?Why do we want to share things? What does love really mean to us? I have become fascinated by this area of study, and while I have only read a little of the knowledge available, its basic concepts have proved to be inspirational (at home as well as at work).

Although initially I thought I could have conversations with my team members about how to show their emotions, I was completely amazed to discover that many people have very little notion about what they are feeling; certainly many don't have the vocabulary to describe what is going on in their own bodies. I just never imagined how difficult the acquisition and mastery of emotional intelligence would be without not only the ability to notice, identify and understand feelings, but also an adequate vocabulary with which to communicate about them.

Once I had a conversation with one of my male team members about how he could improve his level of engagement with his team. He had just returned fresh from a holiday and radiated positive energy. He told me how wonderful his time with his family had been. He then described some activities he could do with his team and what results he expected. At one point I interrupted and asked, "How are you feeling right now?" He looked puzzled, which was understandable given my interruption. Again, I asked him how he was feeling at that very moment. He replied something like, “Things are going well; I am making progress.” I again explained I was not asking about that; I just wanted him to tell me what feelings he was experiencing while sitting there speaking with me. He really could not answer the question.

I gave him a few examples: happy, sad, nervous, energized, irritated. He then started to understand, but intriguingly, while he looked perfectly comfortable and energized to me, he could only say, ‘Fine.’

Our conversation became probably the best conversation we ever had. He acknowledged he had never asked other people how they were feeling. He told me about a young woman, a very talented member of his team, who due to her divorce had been going through a rough time. When I asked if he had spoken to her about this, he admitted that he had not. I asked him if he would appreciate his colleagues or boss asking him how he was doing if he was experiencing such a situation. Without hesitation he said, ‘Of course!' He then smiled at me -- he had made the connection in his own mind. If he wanted to engage more with his team, he needed to connect with them on an emotional level, starting by showing concern. He left the room even more energized to try out his new discovery.

Since then I have found that many people, mostly men I must admit, have a vocabulary in their ‘emotions textbook' limited to‘good,’‘ok,’'fine,’‘so-so,’ and a few other similarly nonspecific, generic terms. Maybe I should have been aware of this all along, but at least I know now, and I can begin to put this knowledge to work. The most important consequence is I now realize that not only are people hiding their feelings from others, they are also often hiding their feelings from themselves!

In this area of acknowledging emotions in the workplace, I cannot claim we had made much progress by the time I left TNT, but at least we were trying. Only ‘naturals' like Angelina had fully embraced this concept, consequently helping their team members become more emotionally intelligent in their work.

(selected from In China We Trust by Iman Stratenus, published by China Intercontinental Press in 2018)