A painting from 17th-century China depicting a lady with a duck-shaped incense burner and the accompanying incense cage under her long skirt.[Photo/Shanghai Museum]

The ancient Silk Road had a profound influence on Tang Dynasty China, opening it up to the world.

Imagine an aristocratic lady during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) more than a millennium ago. Exuberantly beautiful, a lush pile of hair spirals from the crown of her head like a pond snail. Dressed in a low-cut, bust-revealing gown with silken luster that accentuates her opulent beauty, she is glamorous and sensuous, and no doubt fully aware of her own allure.

She seeks to further enhance that charm, partly by immersing herself in an aromatic scent that, despite its origin in faraway lands, has become le parfum de l'epoque. Potent and hypnotizing, the aroma not only adds an edge of seduction to the indolence of this well-pampered lady, but also offers a metaphor for an era in Chinese history known for its prowess in nation-building and diplomacy.

Court ladies by Tang Dynasty painter Zhou Fang.[Photo by Yu Jing/China News Service/China Daily]

The Famen Temple Museum, about 110 kilometers from presentday Xi'an - the temple's name means "a passage to the land of Buddhism" - was once the place of worship for Tang rulers. Its director, Jiang Jie, says: "For those in the know, this typical image of a Tang court lady is in itself a reflection of the exchanges between China and the land lying to its west, through the extending route known today as the Silk Road.

"The scent resulted from the burning of spices that came all the way from places including the Eurasian steppes, the Indian subcontinent and the shore of the Arabian Sea. The practice, apart from feeding a romantic need, also had a practical side: the strong smell acted to repel insects, mosquitoes for example, and to make sure that the ladies, while proudly exposing their glacial skin on a hot summer's day, did not have to lose their composure because of a gnawing bite.

"This is very important, because climate scientists now believe that the Tang Dynasty, especially the first half of it between the early seventh and mid-ninth centuries, lived through a general rise in temperatures that, in retrospect, aided the society's propensity for flimsy clothing and fragrant scents."

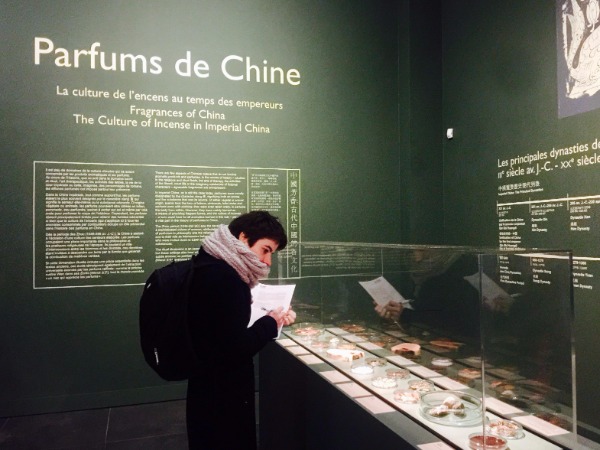

A duck-shaped incense burner from ancient China.[Photo/Shanghai Museum]

Even the fashion sense of the time, with a level of daring unrepeated by any subsequent Chinese dynasty, was formed partly due to this influence from the west, Jiang says. "It seems that the hot wind blowing from the Gobi Desert and beyond reached and tickled at the heart of the Chinese empire."

Stretching over vast areas of Eurasia in today's Mongolia and northwest China, the seemingly boundless Gobi Desert presided over the ancient Silk Road that cut through it. The road itself was first opened by a man named Zhang Qian, who, acting as an envoy for Emperor Wudi (156-87 BC) of the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220), embarked on his westward journey from the city of Chang'an, the Han capital, in 139 BC. The aim was to seek a military alliance with the country of Dayuezhi, against their common foe - the throat-slaying Xiongnu horseman, a large confederation of nomads that dominated the steppe from the late third century BC to the late first century AD.

The mission eventually took 13 years and many twists, yet was never quite accomplished. Still reeling from their previous defeat by those ferocious marauders, the king of Dayuezhi was reluctant to join forces with the Han. But when Zhang Qian returned in 126 BC, he brought back with him the knowledge of a new route that could lead to both military allies and trading partners, and, hopefully, admirers.

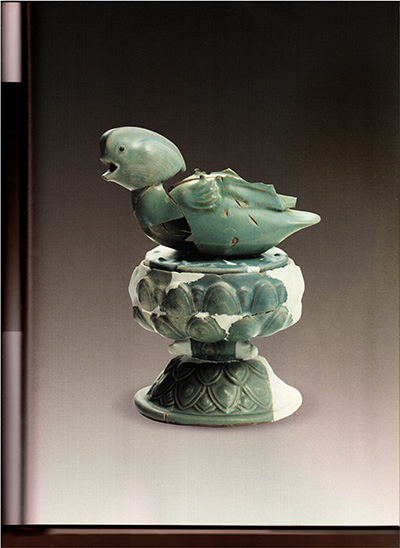

Ancient spice specimens on view at the Cernuschi Museum in Paris, titled the Perfumes of China.[Photo/Shanghai Museum]

For the next millennia, the road, named after Chinese silk, its most famous commodity, was explored by the ambitious and adventurous from both sides, until it became a fully developed transport network traversing Eurasia. At one end of it was the Chinese empire, and at the other end the Mediterranean countries and Rome. The road, with more than a few tributaries to reach the surrounding regions, cut through diverse terrains and disparate cultures.

The traffic on the road reached its peak with the rise of the Tang Empire, which put a lasting end to the four centuries of war and fragmentation that separated it from its equally great predecessor, the Empire of Han. The two golden eras in Chinese history hold up mirrors to each other, in social wealth and confidence, as well as a resulting willingness to know and be known.

And they shared the same capital: Chang'an (known today as Xi'an, the capital of Shaanxi province), from which Zhang Qian set out on his milestone mission, and toward which endless streams of caravans headed, laden with everything that might fascinate and reap a profit, in the centuries to come.

An exhibition at the Cernuschi Museum in Paris titled the Perfumes of China.[Photo/Shanghai Museum]

Spice was on top of that list, even before Tang. "During the Sui Dynasty (581-618), which directly preceded Tang, spice transported along the Silk Road was already arriving in China in huge quantities," Jiang says. "Such was the longing to be overwhelmed by the scent that large carts carrying the burning ashes of the spices were driven across the streets. The idea was to fill every corner and crevice with aroma."

The Sui Empire lasted for a mere 37 years, a lesson not to be missed.

"The early rulers of Tang indeed tried to cut the level of luxury they allowed to themselves and society in general." Jiang says. "But when immense social wealth soon started to accumulate, and when military triumphs pushed the borders of the empire outside, further strengthening safety on the Chinese section of the Silk Road, things started to take on a hedonistic aspect.

The inner mechanism of the scent sachet found in the underground crypt of the Famen Temple.[Photo by Yu Jing/China News Service/China Daily]

"The popularity of spice again soared. People would sit around long tables with big incense burners placed on top."

In another case, when the property of a corrupt high-level official was confiscated during the reign of the Tang emperor Daizong (727-779), more than a few chests of black pepper were discovered.

Ge Chengyong, a Chinese historian and archaeologist, wrote about the use of spice in Tang-period architecture. "People would probably be amused by the black pepper story, but back then, mixing black pepper with mud and using it as building material was de rigueur for wealthy elite."

Other uses of spice came in more discreet forms, but no less ingenious ones. Found in the underground crypt of the Famen Temple, a hollowed-out gilt silver ball with latticed flower-and-bird patterns is believed to have been a scent sachet. What is known today as the system of Cardan's suspension was set inside the ball, keeping it constantly horizontal and preventing the perfume powder from spilling when the sachet moves with the wearer.

A porcelain Sodgian merchant and his horse.[Photo by Yu Jing/China News Service/China Daily]

"Although there is no visible flame, the powder is in a burning condition, turning the little sachets into mini-warmers that people carry in their sleeves, especially during winter," Ge says. "There were also bigger ones, ones for the cold winter night.

"In terms of spices and scents, what really set Tang apart from the eras that preceded it and followed it was a fever for something foreign that had effectively burnt through various layers of society. The sparks of enthusiasm also fell into many other areas, which, put together, signaled an openness more associated with Tang than any other period in Chinese history."

One example is Buddhism, another famous import along the Silk Road. In retrospect, it may not be entirely surprising that the spice culture and Buddhism fed each other during this time.

Tang Dynasty (618-907) silver incense burner.[Photo by Yu Jing/China News Service/China Daily]

Most imported spice was turned into wafts of holy smoke during religious activities in Buddhist temples, including the Famen Temple. On the other hand, part of the few remaining scent-mixing recipes dating back to that era can be found today in Buddhist writings from the same time.

The vitality of these commercial and cultural exchanges can be glimpsed from the lines of the Tang Dynasty poet Nie Yizhong (837-884): "No horse ever stops to rest/and no night spent without the sound of rolling wheels filling the ear/There are fewer grasses underfoot/than grains of dust on the clothing."

The poem is titled The Road to Chang'an, and the dust-covered men who were constantly goading their horses forward were the Sodgians, middlemen who monopolized trade on the Silk Road between the forth and the eighth centuries. (Nie was one of the more than 3,000 Tang poets of his time who visited and wrote about the sprawling Tang capital. Chang'an, covering 84 million square meters, was six times the size of Rome and seven times that of Constantinople.)

Song Dynasty (960-1279) waterbird-shaped porcelain incense burner.[Photo by Yu Jing/China News Service/China Daily]

As merchants and messengers (for the kingdoms they passed by en route), the Sogdians were not taken lightly by the Tang emperors, who set up specific departments within their government to handle their matters.

Rong Xinjiang, one of China's leading Silk Road experts, says it was common for the Sogdian merchants to come in the name of diplomatic envoys.

"Tang-era documents unearthed along the Silk Road show huge mission groups that could include up to a thousand people. Needless to say, only a few of them were real diplomats, although it is important to note that commerce and diplomacy were never quite separable. To trade in the name of paying tribute - since the opening of the Silk Road, this practice had allowed many businessmen smooth entree into China."

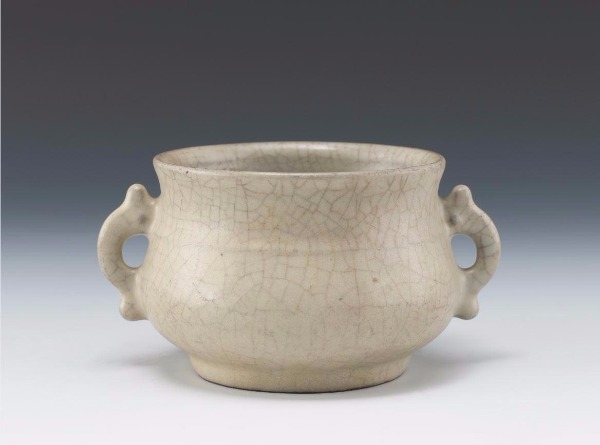

Song Dynasty porcelain incense burner took its shape from the bronze ware of the Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC).[Photo by Yu Jing/China News Service/China Daily]

However, that does not mean the Tang court could be easily fooled when it came to money matters. All "tributes" - be it a gilt silver plate or a roaring lion - had to be strictly evaluated by a panel of experts to decide their value, Rong says. "Gifts" considered most precious would be sent directly to the emperors, who then would grant a reward accordingly.

"The reward often came in the form of Chinese silk, books, papers and copper mirrors, whose making engaged many imperial workshops. But of course, not all trade was aimed at the ruling elite. We have reason to believe that plenty of commercial activities went on at the grassroots level, although little of that was recorded by history."

Extensive exchanges aroused society's curiosity, which in turn fueled a sustained passion for things exotic. The resulting impact, Jiang of the Famen Temple Museum says, went far beyond the thoughtless embrace of luxury.

Remnants of fortresses built along the ancient Silk Road in today's Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.[Photo by Chen Jiansheng/For China Daily]

"It's true that the Tang Empire, especially its first one and a half centuries, is noted for a penchant for luxury and a taste that veered toward the glitzy and glamorous. From gem-embedded gold and gilt silver wares to widespread wine culture and the famous hot bath, a lot that evokes Tang could be traced back to that famous road."

Jiang was referring to Huaqingchi, or the Huaqing Pool, a hot spring-endowed imperial palace 30 km east of Chang'an. For more than a decade it was the winter resort for the Tang Emperor Xuanzong (685-762) and his beloved concubine Madam Yang.

Jiang believes that the bathing tradition hails from West Asia and beyond.

"But what went on the surface, including the upbeat mood and the freewheeling spirit, seeped deeper to form a quality that revolutionized society," he says.

Map whose dotted red lines indicate the terrestrial Silk Road.[Photo by Chen Jiansheng/For China Daily]

One example involves the social status of women, considered having reached a historic high during the Tang era. This is not only evidenced by a fashion that celebrated femininity, fashion believed to have been influenced by the Persian style, but also by the fact the Tang witnessed the coronation of Empress Wu Zetian. Unlike other powerful women in the country's history, the empress ruled not from behind the curtain, but the throne of her own.

Emperor Taizong (598-649), the greatest of all Tang emperors to whom Wu was once a concubine, proclaimed himself "The Heavenly Khan". (Wu, who was remarkably younger than Taizong, later married his son and successor, Emperor Gaozong, mothered by Taizong's deceased wife. Her ascension to the throne took place in 690, seven years after Gaozong died.)

Tang Dynasty tortoise-shaped incense burner from the Famen Temple Museum.[Photo/Shanghai Museum]

"The self-designation tells as much about the attitude of the emperor as it does about that of his people - they were ready to take the world under their wings," Jiang says.

"If there's one word to describe the Silk Road, it's fluidity. The constant influx of 'foreigners' into Chang'an and other major cities of Tang not only broadened locals' outlook but also instilled into the society a world vision, a vision that translated into a strong assimilating force.

"As a result, many who had come just to trade eventually stayed, long enough to start calling themselves the people of Tang."