I have done many projects in China. I think three buildings by far are my favorite: Dalian University of Foreign Languages, the Nanjing Youth Science Center and the Bank of Communication head office in Nanjing. I also liked my stadium for Hockey and Tennis design very much, but unfortunately it never worked out. These projects are my favorite because they turned out to be closest to my original designs. The clients understood quality in architecture and did not compromise. They did not accept the local design institute to change things around as they pleased. I would say for Dalian University of Foreign Languages, 70 percent of my designs were executed. That rate is maybe 80 percent for the Science Center and 100 percent for the Bank of Communication.

I finished the project for the Pudong Youth Palace in Pudong in 1995. At the beginning of the following year, I turned inactive from working in China after the death of my son Nicholas. It was only later, when I met Qi Jun, that we started cooperation by working on the Dalian Foreign Languages University

During the 1990s, China began renewing its push for marketization at a time of widespread beliefs that it would return to the planned economy. Many foreign investors left during this time, each worried that the country's political stability was only temporary. I myself, though, have always been convinced that China will never move back in history. It will only go forward, toward a new horizon with an ever-more democratic style of governance. But many others, including people on the mainland and those in Hong Kong before the 1997 handover, did not share my view at the time. Despite and amid China's progressive opening up process, its young architects left the country in large numbers, each convinced that they would succeed, earning money and fame in North America. But that was not the case. Developments in North America, fostered after the WWII, were in a state of decline following diminishing population growth. In comparison, China has a vast population and needs urgent, complete redevelopment. There, not North America, is where all the opportunities were.

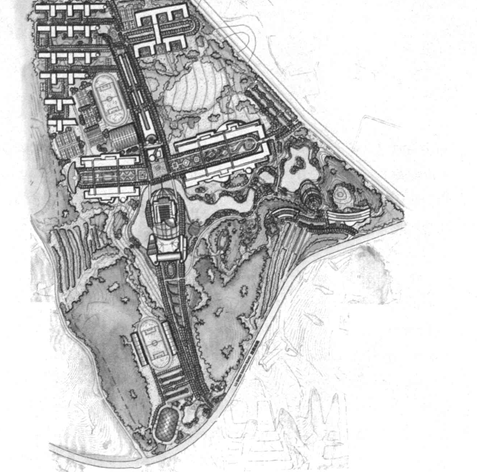

Qi Jun was one of the people who saw that trend clearly and convinced me to get back to work in China, where there was a competition going on for the Dalian Foreign Languages University. The competition project was initially for an urban design master plan. Then the clients wanted the master plan to integrate with the landscaping. So we, together with the EDA, which was looking to expand its business in China, formed a team and took part in the competition.

Personally, I had always been very interested in designing a university campus because when I was teaching at Florence university, I did a lot of research about the European universities and visited several campuses in England: Cambridge, Lancaster and University of Lethbridge. So the project in Dalian was a great opportunity for me to put in practice what I had studied and learnt during my visits to those campuses.

Jim Qi and Franco Scolozzi, take a photo with the submission model of Dalian University of Foreign Languages.

As we made a presentation of our designs and experience in China on the campus in Dalian, I discovered that Mr. Zhou, the vice president of the university, had spent several years in the United States. He spoke fluent English and was very open mind to have foreign architects on board with new ideas. Coincidentally, this was also the time that China as a whole was looking toward to buildingits renewed international image, a process in which official architectures are constantly looking for foreign expertise for new ideas. Chinese architects at the time did not know how to blend local culture with the global culture. The aforementioned example of modern buildings boasting pedestrian images of typical Chinese roofs during a particular period in Beijing's development was a classic case of not blending, but simply overlapping one thing with another. That was, in a sense, what our effort was about-not just bringing modem ideas to China, but also understanding its own culture and not interpret it in a literal, layman way.

The ground breaking ceremony of Dalian University of Foreign Languages (from left M.Zhou, vice-president, Franco Scolozzi, DUFL president, Dalian Party secretary, my long standing partner Arch. Jim Qi.)

I believe I succeeded in the design of the campus by introducing a concept that does just that- metaphorically bringing some elements of the Chinese tradition. So when the jury looked at the project proposals, ours was very different from all the others because there was a metaphorical link between the past and present as well as a modern idea that brings back the Chinese tradition without being a pedestrian imitator. The particular concept we introduced for the Dalian Foreign Languages University was to take into consideration that Dalian has a very beautiful natural environment, such as hills that until then remained untouched by development. It is a city surrounded by hills. That was a very wise thing that the Chinese government did-they refrained from exploiting hills for development purposes liked it happened in most western countries. In the western world, much beautiful natural environment was damaged because the developers did not respect nature and the planners did not impede this exploitation. Sometimes hills were built into something else and lost their appearance and character in the process. In China, though, most of the mountains and hills are not built. In this particular case, we understood this aspect of Chinese culture and we decided to respect it. This site was surrounded with hills in much the same way as like a valley. Thus, our concept is one that seeks to preserve all the hills and have the project itself built in the valley.

Dalian University of Foreign Languages Master Plan.

We also introduced the concept of storm water management. At that time, all rainwater was to be drained directly to the sea. Our idea was to introduce storm water management on this site and recuperate the water to the bottom of the valley and make of this water a lake. After learning that dragon carries a particularly unique meaning in Chinese culture, we came up with an idea of making this lake a metaphorical representation of the Chinese dragon. Aside from that, we introduced the concept of City Gate as a metaphor to the citadel of culture, which became the administration building.

It was that sense of modernity, tightly blended with local traditions that made our project proposal a success. We won the bidding after a fierce competition with Tongji University. Since even the mayor could not make the decision, the project was taken to the provincial level for final judgment and Bo Xilai, then Party chief of Liaoning, made the final say in our favor.

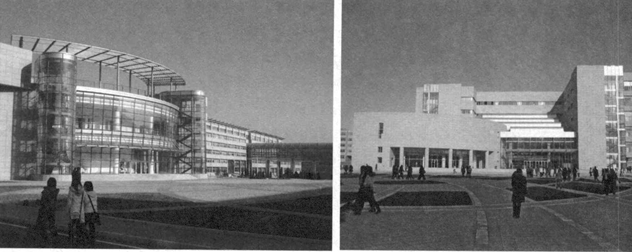

The campus of the newly built Dalian University of Foreign Languages.

For this project we designed the master plan and conceptual image of all the university buildings. Besides introducing this new urban design concept that took into consideration the square used in Dalian and the storm water management, we also introduced several aspects of Chinese culture. One of the things I noticed about architecture in urban China-especially in Beijing-is the gateway, or the big gate to enter a city. We introduced that concept into this project by making the administrative building the symbolic gate to the campus. Behind this gate is a public square that holds two types of functions. It can be a place of gathering for all students during Spring Festival or graduation ceremonies. In the arrival square behind the Administration building, we located the theater, which was designed in a way that it could open on the square. All these enabled any number, even a very large number of students to participate in university events in an open environment. Bo and the jury liked these concepts of ours. The university's president approached us too and said he was very pleased and appreciated our project because we seemed to understand Chinese culture even better than the other competitors, which included two or three local design institutes, include that of Tongji, and the Japanese, Singaporean and American firms. Not only the officials, a referendum in which students and professors took part also saw our project coming out on top.

It was from the success of this initial master plan that the university's vice president, Mr. Zhou, extended an invitation to us and we were commissioned to further design all their buildings. As it was a huge undertaking, I decided to open an office in Dalian. This was also at the suggestion of Mr. Zhou, who, speaking on behalf of the university, told us that they wanted constant contact with us and did not want us to return to Toronto to do the work, and that maybe we could open an office here. I, of course, was all open for it. So we opened an office with our Chinese partners in Dalian, where we worked for almost half a year to design all the buildings. And eventually, the implementation of most important buildings, such as the administration (the gate-way building), the library, and the traffic circulation turned out to be quite well.

The students' activity center and library at the Dalian University of Foreign Languages.

Any wanderer would come in from the main street and hit a processional route that takes them to all the university's buildings. But first, they have to go through the two gates of the administration building to get into the main square. The administration building is a bridge on top of a one-way access road. The road that goes out of the university is also bridged by the building. In other words, we have one road that comes in, one that goes out, two streets, one-way circulation. The university liked this design very much, because it gives an idea of a citadel there, out of the main settlement of Dalian. This campus is on the way to Lǚshun, a city about 20 km outside of Dalian. The buildings are surrounding by the hill park that belongs to the university. The library is opened towards the square. The doors of the theater can slide open so that people outside could take part in what is happening inside. We introduced the concept of a main square and designed a secondary square, the student square. Then we designed the building around those squares. We ended up designing the library five times because our Chinese counterpart wanted us to produce different solutions to compare with. But in the end, Mr. Zhou acknowledged that our initial design was the best one. So we went ahead with it.

My design philosophy is such that I do all the research and thinking for a good design. Therefore, if I am asked for design alternatives, I have to find a way of developing a different concept that goes around the original idea. You simply cannot design alternatives that are intrinsically different from the original idea. We became very good friend with the vice president of the university, but the design process was frustrating because of this continuous request of change and producing alternative solutions. For the library, the theatre and some other important buildings, about 70 percent of our design concept was followed, whereas our plans for many others were changed dramatically and the final result not even close to what we had in mind.

This campus is capable of having 10,000 students-the maximum is 15,000-and so it's like a small town. In order to fulfill the time requirement, the University decided to spilt up the production of the buildings' design into several groups of buildings and give them to five design institutes, each of which is responsible for the production of working drawings for one phase of construction.

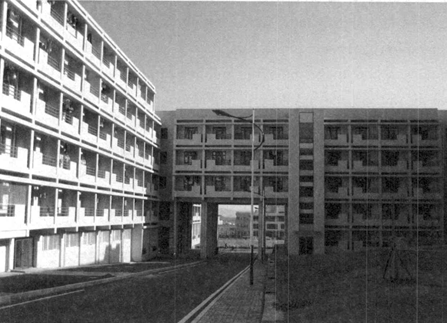

The students' dormitory building at the Dalian University of Foreign Languages.

A huge crew of construction workers worked day and night and managed to have everything finished and the students moved in to the new site from the downtown campus in about two years. Everything was done very fast. Unfortunately though, that incredible speed proved to be a negative element in the sense that some of the details and design qualities were compromised. But it was not so bad. The design experience of this campus was a much better one than in Pudong, where the shape of the building turned out to be the same but the appearance and details were totally different. For the Dalian project, an average of 50 percent to 70 percent of our original ideas were implemented. In my view, we managed to achieve so much precisely because keeping in mind of what could have gone wrong, we insisted that the university keep us as consultants to monitor the design development and the construction of the buildings. They agreed with our request and this proved for them a guarantee that our design was respected throughout the process.

The bright students' dormitory building.

I recall walking around the campus one day and taking pictures all around. A young student stopped me and asked why I took pictures. I said I am the architect who designed this building. The young student exulted with enthusiasm and said at last, she found out the designer of this building. She told me this campus was one of the most beautiful campuses in Dalian and one of the best places she has been to. She told me that everybody liked the atmosphere here and enjoyed staying there. When we designed the dormitory, for instance, we were concerned that the students may not be able to find their residence from piles of similar buildings. So we introduced colors in the balconies' walls. That way, the students would be able to distinguish one building from the next and find their way to their own rooms. In every building we introduced a different combination of colors so every student dorm had its own identity, its landmark, its legacy. Red, yellow, blue, green were used as primary colors. I wanted everybody to like that and feel comfortable in that setting. And, of course, colors bring comfort, warmth and can help uplift spirits during gray, chilly winter days.

One way or another, we received a lot of flattering comments from design institutes of other cities that visited the foreign language university in Dalian, which over time became one of the topic examples of modem campus in China. I think that was the biggest development and probably one of the most successful designs that I had done for China at that time. It brought great satisfaction for me too-it was another realization of my dream and life goal to create nice environments for people to live in. We took lessons from a medical campus designed by a Japanese architect across from the highway to the Dalian foreign languages university. Compared to ours, the environment there is quite depressing because the same gray color-was used everywhere. That's partly why we used different stone colors so that every building could have a very pleasant appearance. We used warm colors, keeping in mind that the gray color in the other campus would become grayer during the winter and produce a discouraging effect. Grayness has been a definitive aspect of Dalian's winter. It becomes depressing for anyone in an environment where everything is gray, particularly for those who study medicine and deal with patients and the deceased. Studying and living in a place that is gray all around would make life very gloomy. So we tried our best to introduce colors and use different stones with different colors so as to make the Dalian Foreign Languages University a happy place to study, to live, to be, an example, in other words, of how to design a suitable living environment for people.

I have previously said that many cities in China look the same. The distinctiveness in Dalian, though, lies in its concept of squares. There is, indeed, the Tiananmen Square and lots of other squares in the Forbidden City of Beijing. But the concept is basically lost in most modem cities. Dalian is not one of them. This might be because Liaoning province, Dalian's superior administrative region, had been historically influenced by the Russian and Japanese cultures and the first master plan was done by a German planner. On the outset, too, Dalian is very different from your average Chinese city. The climate is different as it is a coastal city with a more pleasant climate than cities in the inland. It also boasts a lot of green areas and hills that at the time were not exposed to large-scale development. There was, in a word, a lot more green around in Dalian compared to many other similar-sized cities in China. In 1995, the city planners and architects recognized that the most important thing for the environment and the city was to retain its greenness. From then on, they had tried their best to make the city "greener."

When we speak of squares in China, their function was, in many occasions, regarded as a display of power of the emperor. Many historical buildings such as the Forbidden City were designed as if a box within a box and a courtyard with a courtyard. We carried on that idea of the courtyard in our design of the students' residence in the Dalian project.

Xinghai Square is the landmark architecture of Dalian. It is also the largest city square in Asia.

I have, over the years of my stay in China, found that the traditional concepts of the square and the courtyard are lost in the cities I worked in, for example, Guiyang and Wuhan. I had a meeting a few years ago with Beijing's party secretary. We talked about architecture and planning. He sort of complained about lots of courtyard houses in Beijing being destroyed. The developers would buy the land from the government and, in order to maximize profit, they demolished everything, the fantastic courtyard houses for example, and replaced them with skyscrapers. The party secretary said things were changing because increasingly, foreign architects working in China as well as domestic architects educated abroad were questioning the demolition of the city's unique heritage. An influential movement that sought to preserve courtyard houses was gaining around in Beijing, and the demolition of traditional quarters was eventually called off. In Shanghai, too, several historical areas at the risk of commercial development were preserved and restored. As a nation, China is going through the same stage of development we did in Europe. After the WWⅡ ended in 1945, people all across Europe began taking down buildings of architectural significance without a serious consideration of what can and cannot be demolished. A few architects then fought back, leading a public opinion that points out any attempt to wipe off history would be a disaster. Hence started a great movement of retention of historical buildings and buildings with architecture significance. That is, we too went through the demolition stage and then stopped at a certain point. The United States and Canada went through the same thing. Very interesting buildings in Toronto were demolished and replaced by modern buildings with a utilitarian nature and far less esthetic value. Lots of important monuments were lost. China is going through the very same experience. Fortunately, having learnt this, we are able to pass on our experience to Chinese planners and decision-makers, so that the same mistakes could be avoided whenever possible. We were very critical when we talked to the Shanghai and Beijing authorities. We talked to them and explained that what they were doing was a mistake and basically a repetition of errors in North American cities that put highways in the middle of the city 50 years ago.

The Imperial Palace in Beijing, the exceptional ancient Chinese architecture masterpiece. It is the largest and completely preserved existing ancient building complex in the world.

When I was working for the Dalian project, I was introduced by the Ontario government official to a Beijing-based architect who was interested in working with me. The Ontario government was very active in exporting culture and technical know-how to China, and played a very important role in introducing us to potential Chinese clients or Chinese people who would direct us to potential clients. After I was introduced to the agent, a structural engineer, I went to Beijing and was invited for the competition of an Olympic Games Venue, the tennis and hockey stadiums. This was a big undertaking, one for which the design was to be completed in one month. The site was divided into two sections, one for hockey and the other for tennis.

A group photo of Philip Wong, Consulate General of Canada in Shanghai, Ms. Julia Ningyu Li, CEO of Bong College, Franco Scolozzi, Mrs. Hope Jaglowitz, Director of MEDT, Mrs. Robin Garret ADM, Mr. Gould, Derictor of MEDT.

Upon receiving the documents, we started to look for a local design institute partner who would work with us in the subsequent phase of design. In the meantime, time was ticking and we ended up with 20 days left to submitting the documents for the competition. I contacted Beijing Yejin (Metallurgical) design institute, which was in charge of completing the working drawings for the Nanjing Youth Science Center. They have an office in Shanghai. I called one of the executive echelons, Mr. Wang Yuhong, who was very enthusiastic to cooperating with us again. They shipped a team of six people from Shanghai to team up with the six people from my office. We worked day and night and finally managed to meet the submission deadline. The weeks were well spent. The Yejin design institute lent us some space in their head office, where we started to work together with myself in charge of the design. Some of the people we worked with on the Shanghai project also came. I came up with the concept within a week.

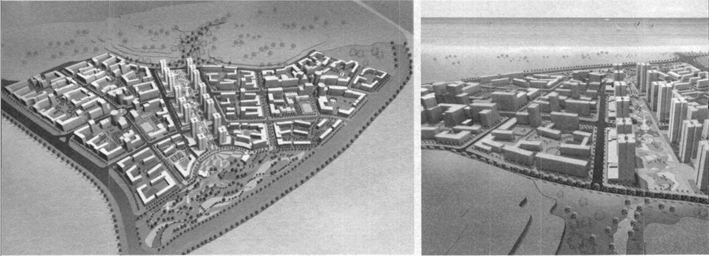

I decided to put the road underground, connecting the two sites together. We introduced the concept of Chinese garden surrounding the stadiums, and around that, the European garden. Storm and wastewater management was also part of the package, which included creating a lake that took the shape of the Chinese Dragon. In the initial stage we came out as one of the three best designs among 69 submissions from all around world. An American firm, a Japanese firm and us were all that were left to compete for the final solution. The advantages of our design solution lied in joining the two sites together, the garden-within-a-garden concept, and the buildings themselves, which were a metaphor of the phoenix for the hockey stadium and the egg for the tennis stadium. Our design was published on a Chinese architectural magazine and our project became part of the permanent exhibition at the Beijing Museum of Architecture and Planning.

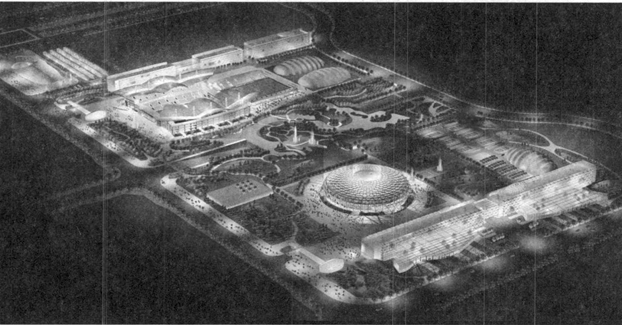

The master plan of the National Tennis Center and National Hockey Stadium designed by Franco Scolozzi.

Wang Yuhong, Da Shan and Franco Scolozzi during the Ontario Trade and Investment Mission to China in 2005.

Unfortunately, due to budgetary concerns, the second stage of the Tennis and hockey stadium was cancelled, and we got paid a design fee that covered the production expenses. Still, I was very proud of our work. This was the shortest time we took to design a project of this magnitude. We thought it was an impossible, but everybody was enthusiastic and worked so hard to help the dream became a reality. Even Mr. Wang Yuhong was, in the beginning, pessimistic when he came and talked to me. He said: "Franco, we will do this for you but we don't think we will win. It's impossible. First of all, there are too many competitors. They're too strong and the time is impossible. How can we do it in 20 days?" I told him nothing is impossible if the team works with enthusiasm and passion. We worked a solid 12 hours everyday during the 20-day span. When we submitted our proposal, I sneaked into the submission hall to look at the other competitors' project one by one. It was only then that I suddenly realized that ours was one of the best, if not perhaps the best submission. The press echoed that view. The architecture magazines and the newspaper that published the competition all listed our project as the top candidate. It was an amazing experience, not least because contrary to most other competitors from the US, Germany, Japan and Denmark, this was the first time we designed a stadium.

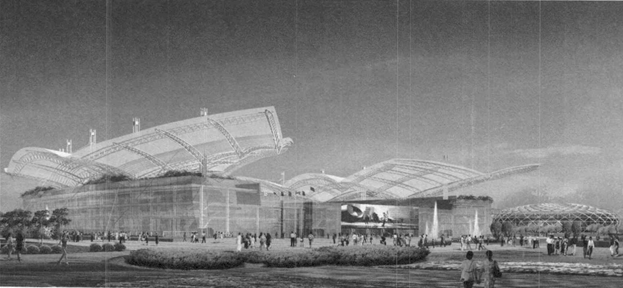

The National Hockey Stadium designed by Franco Scolozzi.

Up till today, I have designed around 40 projects in China. The most important for me has been the design of new communities. This was simple in a way, but also difficult in that the settlement must be able to give its inhabitants a sense of belonging. In each of the communities we designed, we introduced components of Chinese culture or metaphor as well as the concept of pedestrian precinct area. We thought China was lacking very badly of areas where pedestrians could feel comfortable walking, shopping and simply having fun in with total safety. This was due to a variety of factors, inch ding a large population base and an increasing number of cars, many of whose owners do not tend to respect pedestrians, although traffic regulations stipulate otherwise. In my experience, very seldom do Chinese drivers stop and let pedestrians pass the road. In most cases, they pass first, without extending any consideration to the pedestrians or the consequences they will have to bear should an accident occur. I really felt that we must do something about it and create pedestrian areas where cars are not allowed to go, where trucks providing supplies to neighborhood shops can access the service road and avoid creating jam by using a lane of traffic.

Nanjing road in Shanghai.

We tried to apply these principles to each community we designed here. In our design of the master plan for the residential area of the Dalian Nuclear Energy Power Plant, for example, we paid close attention to the environment, creating lots of green space, and cared about pedestrians in a way that minimized land-use and maximize green areas. Additionally, we used storm-water management to retain the water and recycle it for use for irrigation purposes, so people no longer had to dig into the city's water supply just to water the plants. We used one-way circulation street and we use the concept of storm water management, the pedestrian environment, and shopping area where cars are not allowed to drive. We won the competition for the master plan of the Dalian Nuclear Energy Power Plant because of all these aspects, and consideration for understanding Chinese culture, bringing in the best idea and most advanced idea about the environment, caring about people, caring about life, caring about children, caring about families. We started to apply this principle 8 to 10 years ago, when public consciousness about conservation and self-sustainability was just gaining ground.

Two of my projects for planning new communities in China are most memorable. Both are located in Dalian; each is significant in professional activities on community planning in the country in its own right. One is the Qianguan community; the other is the Longwang Tang community. Both plans are very interesting in their locations and the presence of water on site.

Francoo and his son Mathias Scolozzi take a group photo in office with their partners.

On the personal level, too, these projects were significant to me because I worked on both of them with Mathias, my son. Without any pressure from me, Mathias, who has a degree in filming, pursued a second degree in architecture. I think this may be because he grew up in an environment where people talked about architecture all the time. My wife Doris and I worked together for a certain number of years and built and designed our own house. That influence on the children cannot be underestimated. It was only because Nicholas, my other son, studied architecture that Mathias wanted to go for something else as a major. However, it was always in Mathias' mind to study architecture, it was one of his choices that he had put to a side, I do not really know why. Eventually he decided to take a second degree at UBC, I was secretly happy about it because he could continue the family tradition and carry on the "flame."

Mr. Dalton McGuinty, Oremier of Ontario and Mrs. McGuinty, Franco Scolozzi, Mathias Scolozzi attend the Ontario Trade and Investment Mission to China in 2005.

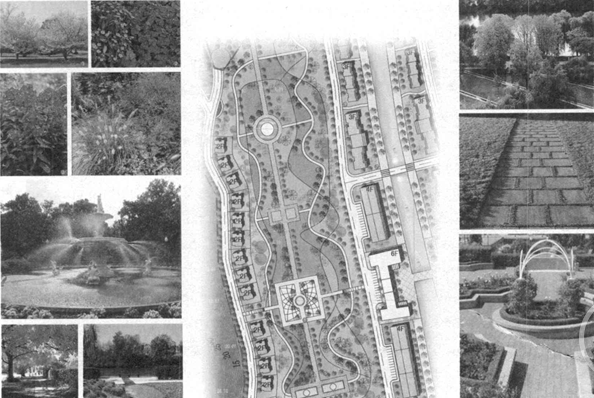

When we first visited the Qianguan community, there were only a few obsolete houses. I think the government was interested in cleaning up the site and turning it into a new development. The site was very beautiful. It was defined by two highways on the south and west side, and on the north side was a hilltop. So we proposed to preserve the hilltop and turn it into a park for the community. Then we decided to not only keep the creek, but also make it into a feature, the central axis of this development. The central axis was basically constituted by a continuous linage of parks that bridge the roads in a way that pedestrians will not be disturbed by or interact with car traffic. With this central park and pedestrian environment, we connected the park on the top of the hill to the bottom part of the site, which had a stream much wider than on the top. The government has also opted to preserve the bottom part of the site as a park to protect housing development for the immediate adjacency of the streets. We followed the instructions, kept the lower part of the site in the south and, using the existing creek, we created a lake. That will convey all the rainwater of the whole site. The north site was designed so that the rainwater drainage would convey altogether into the pond. All this is very important for Dalian because in general, Northern China is extremely dry and is constantly hit by severe droughts. Southern China, on the other hand, boasts a lot of water. This is exactly the opposite in Europe: lots of water in the northern part and very little water in the southern part.

The plan for Qianguan Community in Dalian jointly completed by Franco Scolozzi.

And consequently, water is a very precious element that we decided to keep instead of drain down to the sea. We could use it for the lake or to irrigate for the gardens so that they will always be green. The main concept of this Qianguan community was to introduce the central axis on both sides of the site, we developed a mixed-use concept of podium that would contain commercial facilities. And then on the top, on the northern part of the site, there are residential buildings. On the lower part, there are also residential buildings. And the central section had office buildings. The intention was to create a place where people can live, work and play. This is a new concept we introduced to conserve energy and reduce pollution in the cities. I tend to believe that by reducing daily trips between home and the workplace, we reduce pollution, noise and dust--all of which have troubled China for years--and thus create a better environment.

Along the central axis in the Qianguan community, we have the pedestrian street flanking the gardens, around which the shops would open. And on the east and west sides of this central axis, we designated the place where the supply for shops would take place without interference with pedestrians' movement. Car access in these areas would be allowed only for emergency purposes or supply at certain hours of the day so there is no interference with pedestrian activity.

Dalian Longwangtang project integrates the community with natural scene to forge a "garden community"

Fundamentally, we want to integrate nature with urban space. Another example of this is that we introduced the concept of courtyards at the level of city blocks. In the middle section of these courtyards, there were park or gardens. So every building had its own courtyard, which is at times enclosed and at times open and accessible to the apartment. That means in the whole community, people would be able to walk between courtyards from one building to the next crossing parks. Of course, we have divided this development in several city blocks. Within them, there was a pedestrian park. So the people can move from one residential building to the next without interfering the traffic. This was our main concern-to pay utmost respect to the pedestrians in a times when drivers too often become the center of action.

The second project was the Longwang Tang community. In many respects, that community was more the work of my son, Mathias, than that of my own. All I needed to do was to describe to him what I thought the principles of this community ought to be. The rest he would carry out fast and efficiently. The result was a harmonious bond between the mountain, the water and the community.

Sakura garden extension master plan of Longwangtang, Dalian.

The Longwang Tang community is a valley between quite beautiful hills. The Sakura Garden, very famous for its cherry trees, is situated on one side of its gate. There are mountains on both the east and west sides of the site. And on the north side there is a dam, where the reservoir supplies drinking water to the city of Dalian. When the water reaches a dangerously high level, local authorities would open the dam and let the water flow. The side is close to the sea. Because of high tide, the city has built a small temporary dam to stop the water from going further upstream.

The concept that Mathias and I developed was to revive the dry stream. We did not want to use the reservoir because it is a precious good that needs to be preserved. So what we decided to use was a storm water management strategy to collect rainwater, drain the entire site and dump all the water in the creek and, perhaps using the dam, separate salt water from fresh water form a canal so that the creek will always be filled with water. We also expanded and enlarged the canal in the same way the canals in Venice are. Along with the canal, we introduced commercial, residential buildings. And on the east and west sides of the canal, we put apartment buildings with green courtyards. On the outer edge, the foothills, we developed villas that are located slightly higher than the other buildings. From there everyone can have a view of the valley. We did, however, keep the hillside intact because it had been wonderfully preserved and we want to keep it that way for the sake of the people living there. But unfortunately, the developer, keeping in mind the price he had paid for the land and the future financial returns of the project, demanded us to increase the density of the building. It was clear to us, though, that increase in density would be extremely detrimental for the aesthetic view of the valley and hills. So we did not follow their instruction completely; but instead tried to work around it.

We decided to locate the towers at the very end of the site toward the sea. Then we developed a welcoming center at the entrance from the highway to Lǚshun. It was a square built along the lines of an Italian square, surrounded with buildings where people could come in, park their cars underground, and move up to the Sakura Garden to enjoy its unique beauty. And then, we relocated the people who were living on site along the Lǚshun highway, where we put both commercial and residential buildings. Only few smaller, low-rise residential buildings were now up the hill and would not interfere with the view of the mountain.

(selected from My Practice of Architecture in China by Francesco Scolozzi, published by China Intercontinental Press in 2018)