Parhat Haliq: My band consists of musicians from all parts of the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Turkey. It’s great that music could put together people of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds!

Many Xinjiangers have fond memories of a bridge or a river, and I am no exception. The river of my childhood was inseparable from memories of my parents, my play pals and my early living experiences.

I grew up in the residential area of Bayi Steel Works in Urumqi, Xinjiang, and near where I lived was a swollen river that could easily spill over in summer. When my playmates and I went swimming, we would often fail to notice an oncoming food until we saw our gear on shore being flushed away. By the time I was about eight years old, my dad began telling me not to play in the dangerous river. But I turned a deaf ear to him and kept going any way during the summer holidays. We played a cat and mouse game in which I often got caught and had to have it hard.

Some people might be amazed how meek my dad looked and how quickly he could smile, but he was actually very bad-tempered and strict with me.

One scorching day in summer, I sneaked away on my mom’s bike and came with two friends to the river to swim. When it occurred to me that a relative of mine just across the river had a good harvest of watermelons and cantaloupes, I decided to go visit that relative with my friends so we could have some. As both of my bike tires punctured on the bumpy dirt road, I had no choice but to walk there, only to confront a man with a long and thick whip in hand. It was my dad!

I ran back as fast as I could, my friends trailing behind. My dad hounded me and lashed at my back. Though I almost passed out by the time I had reached the edge of the river dam, my dad had no intention of lessening up in his pursuit. “If you keep chasing, I will jump into the river!” I yelled as I couldn’t stand it anymore. “Expect more licking then!” He yelled back. Eventually, he chased me to the entrance of our house, lifted me up off the floor and carried me straight indoors. Following that, he tied me to a bedpost, headed back to work and did not untie me until evening. At bedtime, I overheard my dad saying that if I did jump into the river, he would have done the same and that we both would have perished in the river.

My parents took a laissez-faire attitude towards my education. They had no special demands on what I must do after growing up, nor did they press me to study hard. They just wanted me to work hard, get married and have kids and lead a normal life. Today, I teach my kids much the same way my dad had taught me, whether in attitudes towards life or towards other people. Before going ahead with something, I would ask myself what my dad would do if he was put in my spot. Though he has passed away, he has always been an invisible adviser to me.

I had spent a lot of time studying, painting, and writing music in the riverside woods because it was very quiet out there. So, the wooded riverside meant a lot to me, but when I revisited it some time ago, I was chagrined to see a lot had gone or changed.

In my neighborhood, I was known as a kid who “walked around with a guitar every day.” I also had a harmonica that I enjoyed playing. After watching Jimmy, an Indian movie whose hero was a guitarist, I made a makeshift guitar with a broom and started imitating him. I had my first guitar in or around 1989, and that was when I started copying a very influential Uyghur singer who played the guitar and sang at the same time. In fact, I imitated whatever sounded sensational and powerful to me. I never thought about having a career in singing, though, nor did I even think of it as a vital part of my life. I sing wherever I am just because I want to express my feelings.

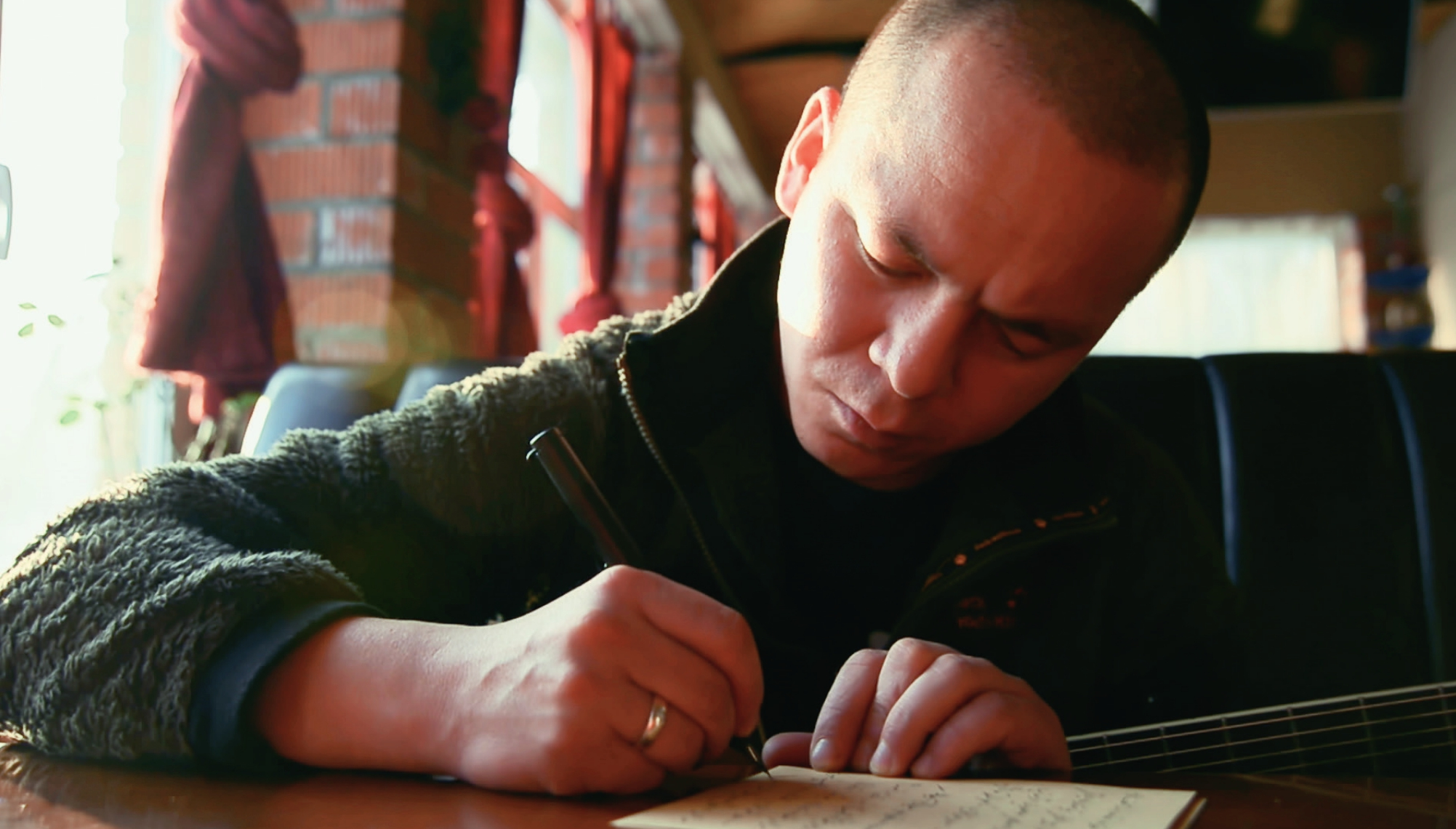

I have a band called Yogurt Band, and I certainly want to give big concerts, but I don’t take it that serious because I never care how much money I make with music. Yogurt Band had performed in restaurants and bars for more than 10 years before being noticed by a foreign producer in late 2009. About a year later, the foreign producer invited me and the band over to Germany to perform. The audience reacted warmly and their contagious jubilation touched me in a deep way. Back at the hotel, I called to mind all those I was indebted to. I thought of my deceased parents, especially my dad who did not live to see me married. How I wished I could tell them what I was feeling then! It was in that sentiment that I wrote the song Content. The lyrics, representing teachings of my parents and some of my childhood experiences, were written in less than 15 minutes. The prelude of the music was a nursery tune that I had heard a lot as a kid. It has a very touching effect.

Creative works like musical compositions are usually based on people’s personal experiences and the kind of environment they live in. Today, many people see mountain-climbing as a status symbol. In fact, mountain-climbing is a sports event that involves a lot of team work. It’s a process in which everyone works on an equal footing, regardless of net worth, reputation, or social status.

Every time we go mountain-climbing, we would live out in the mountains for seven or eight days, sharing food and dwelling and helping each other out in many ways. Some wealthy climbers are a little different. They would carry nothing and leave everything with their subordinates. Isn’t that unfair and cruel? Worse still, such people are in the bad habit of littering. Each time they came they would leave a pile of garbage behind and even pick away the snow lotus of Bogda Mountain. While hiking in the mountains one day, I came across a 90-year-old Kazakh who hated to see people litter. “Have as much fun as you want,” he said, “but don’t litter! This is the place where our ancestors have been herding sheep for generations. If laid to waste, where could we possibly go?”

Indeed, many people are rich but have no manners, they are nothing but slaves of money. Those who destroy the beauty of nature are nothing less than criminals-they belong to hell itself.

If people can do well in little things, they do well in their areas of expertise too. The way you do things is the way you live. I let my children feed fish, cats, and dogs, and let them play with animals because I think kids can learn a lot from animals.

In music I never go after things that are overly complicated or lavish, nor would I demand a symphony orchestra to be my accompaniment, nor demand use of chic instruments or a recording studio. I just want to be practical. I use nothing more than what is needed to create a song or piece of music, and I never superimpose any redundancy into something nice and simple. I do not purposely cater to the market, nor write songs tailored to certain people, nor chase fashion with my works. For better or worse, I write only about what I do and think.

My teacher Wang Feng said that he had dreamed of being a good singer the way that Cui Jian and Luo Ta-you was. But 10 years later, he realized that he should just be himself instead of copying other people. Later on, I also meditated on the meaning of personality. Personality is as good as what it does to people and to yourself. Does your personality do any good to you? Does it do any to others? If it does no good either way, then it’s mere garbage. I used to sing whatever I liked to sing. When I realized I had a certain responsibility, however, I began to think if my song is of any value. I began to remind myself that I could not simply write just about everything, because that would stumble a number of people, including your fans and others who might like your music. I’ve seen albums of dirty songs produced by some singers and guitarists that expressed low feelings of life. Music is something that needs to be enjoyed in leisurely moments of peace and quiet. Art can harm you ideologically and in an invisible manner.

Initially, Yogurt Band and I sang only in Uyghur, Kazakh and other ethnic minority languages, and rarely sang any Chinese songs, but now many people want to hear me sing in Chinese. Ethnic minority singers, especially those who sing in their native language, basically hit the same tough road. Later, I found that this has nothing to do with Han people being unable to comprehend ethnic minority music. The problem was lack of access caused by our school and education system. I always feel that the market itself has no objection to ethnic minority music. Ethnic minority artists themselves are to blame for not persisting in it for fear that the audience may not understand them. Why not produce the music first so people can hear it?

Certain things may take a long time for people to accept. Xinjiang music has yet to be publicized. It will not go classic if you only play it at home. Many Uyghur songs are actually good enough to compete at music festivals, but no one seems to know their value.

I have no special preference in the production and singing of Uyghur songs and I do not restrict myself in the choice of musical instruments, regardless of ethnicity or national origin. I don’t think any use of non-ethnic musical instruments can make my music any less my own, nor do I see it as any disrespect for my own ethnicity. But there are a lot of people who think otherwise and set many burdens on themselves and others. They pretend to understand music when they don’t. A lot of things they do have nothing to do with ethnic identity. They enjoy bragging in their own circles, but are reluctant to show their stuff to the outside world.

At the Voice of China Competition, I had the company of some folk musicians who used instruments unknown to the judges. I thought it was the right thing to do and I had always wanted to do that. I decide what instrument to use based on the music itself and my own personal preferences. The greatest change that has taken place after I participated in the Voice of China Competition is that I used to sing in a bar or restaurant at night, but now I couldn’t anymore because any performance in those places could turn into a concert. The problem is, some performances are best avoided, but cannot be avoided. For example, when performance organizers fail to prepare their equipment properly, the singing would fail to produce the desired effect and, to my greatest displeasure, the audience would think the singer has failed to perform well.

When I went on a performing tour in 2015, the organizer of Voice of China came to me and said that they wanted to cooperate with me. Since performing had always been my focus, I could hardly let that opportunity pass. So, I spent quite a few months planning it and preparing for it. It turned out very well.

The band with musicians from all parts of the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Turkey gave a total of 18 performances in 40 days, which had a lot of toll on stamina. At the end of each performance, we were all soaked with sweat, as if buckets of water had been dumped on us. The band had three foreign musicians in their fifties who were quite unused to the environment and the frequency of performances. But they never called it quits. We wept quietly over lunch prior to our last performance in Huizhou, Guangdong Province. After working and living together for so many days, we all felt we were now part of the same family. It was great that music could unite people of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds together!

After a Voice of China competition, I became very busy, but I took time off for home stay whenever possible. A lot of people tell me to work hard and fast before taking a good rest. But why should I? Since we all live but once, we need to maintain a proper balance between work and rest. 2015 was a very busy year for me. 50-day performing tours were very common. When my two kids kept asking me when I would return home, I had to change the topic and ask them what they had been up to and how school was so that they would not wonder when I’d be back. Alternatively, I would tell them directly I’d be away 10-20 days, instead of lying to them that I’d be back the next day. I want to make room for family time lest my kids felt lonely.

Maybe my understanding of “success” differs from that of other people. Many people feel that success is equivalent to popularity, but I think the test of success is “telling the truth.” This is what my parents, who are average workers, have taught me. In fact, most people are just ordinary people doing ordinary things. They are good people as long as they do good to society. People should never be judged by their professions because they are all different and have thoughts of their own. Musicians, artists, and even sanitary workers can have deep thoughts, while those with advanced academic degrees may even lack basic moral ethics. Each person can have his or her unique position, and each is great and valuable. Many people give comments on my Sina Weibo, telling me how they like me and my song. I am much moved but doubtful at the same time. Why would people like me anyway? I am just an average person who loves art, singing, playing the guitar, and talking in a reckless manner. I hope those who like me can love and cherish life and live happily every day no matter what they do to make a living.

My father could neither sing nor play the guitar, but was an excellent worker. He died at 57, but I have never heard anyone say anything bad about him. He was a very successful man. I want to lead a highly successful and blameless life, just like my father. I never thought about becoming a great singer or artist. All I want is do a good job in all I do and be worthy of myself and other people. That’s where my ethical standard stands.

(selected from Xinjiang: Beyond Race, Religion, and Place of Origin by Kurbanjan Samat, translated by Wang Chiying, published by New World Press in 2017)