Lu Xun's "Native Place", where the writer is seen with a probing look and a cigarette with smoke trails swirl like the inscriptions of a pen.[Photo provided to chinadaily.com.cn]

Shaoxing,Zhejiang province, China

It might be said that the great writers of each generation have not only succeeded in evoking a place or people, but also found a distinctive, previously unheard voice through which to do so. From Dostoevsky to F. Scott Fitzgerald, the universally recognized writers of each nation have cultivated a style that is precisely their own, while seemingly representative of the national tenor.

Chinese essayist and translator Lu Xun (1881-1936), and a leading figure in the New Culture Movement of the 1920s and conversations on reform in China, surely sits amid that tradition of voice creators. His essays, including "Medicine” and ”Kongyij” and the various literary journals he helped edit and publish illuminated Chinese society through characters that everyone could recognize but no one had before seen on the page. Kong Yiji tells the story of an aging, ridiculed scholar who fails the xiucai examination and is mocked in the local bar, and implicitly criticizes the futility of an exam-based education system and human indifference. In "An Incident", we confront a passenger whose rickshaw collides with a pedestrian. The passenger must ask, "When do my social obligations to others begin?"

Lu Xun's style is defined by intricate symbolism and philosophical questions as they arose in quotidian life—“how should one act as a friend, a citizen, a partner”—which themselves are interwoven with often melancholic existential realities and historical commentary on China as it moved away from an imperial system and into years of reform and revolution.

These were facets of Lu Xun’s voice, but perhaps the most important was that he often wrote in vernacular Chinese. For centuries, literary writing was composed in the classical style, or wenyanwen, which followed a different syntactical structure from spoken speech and held myriad references to ancient tropes and stories, making it illegible for someone without formal training.

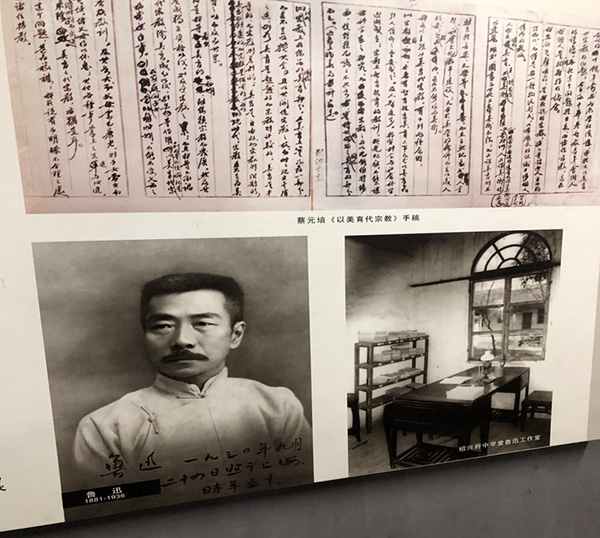

The "three-flavors study" in Lu Xun's ancestral home.[Photo by Jacob Pagano/chinadaily.com.cn]

With the rise of Lu Xun and several contemporaries, prose became a reality, and a new generation of fiction writers emerged. Lu Xun was not just writing in a new voice, but daring to record the voices and speech he heard around him.

Lu Xun is thus recognized as one of China’s first “modern” writers, and his focus on dissonance and alienation, and questions of existence as they overlapped with politics, were radically new.

But in order to see the world out of which Lu Xun was writing, and the traditions which he was negotiating, it seemed important to experience the very space in which he grew up. In what domestic world did Lu Xun live, and did his career in part come as a reaction to that? Could one sense the very same world Xun talked about in his prose, or had it morphed into something unrecognizable?

I headed last week with a few fellow researchers to Lu XunGuli, or the ancient roads and houses where Lu Xun grew up and studied, located in the center of Shaoxing. Lu Xun’s own family home was built in the Qing Dynasty, and it’s surrounded by canals where tourists can hire gondolas, and choudofu vendors call out their best prices. We arrived an hour before a thunderstorm rolled through Shaoxing, which created a dense fog and frenzy to move through the house, as many hustled to avoid the coming rain.

Yet even amid the tourist rush, one has the visceral sense that this was a writer who not only existed on a hinge between two radically different worlds, but also had to work tirelessly to create such a "modern" literary space.

The building in which he attended classes each morning are imbedded with signs of tradition; rows of desks where members of the Zhou (Lu Xun is a pen-name; his original last name is Zhou) family studied together, a hierarchical system of office study arrangement (with the Master and Lu Xun's tutor, ShouJingwu, holding a study and bedroom attached by a private corridor), and a series of canals and gardens that evoke classical literary lifestyles. There’s also the sanwei study, or the study of "three flavors", a reference to the richness that thinkers such as Confucius believed would emerge through diligent reading. Lu Xun’s early education reflected that history—he was trained in Confucian classics and traditional poetry.

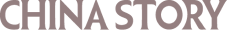

Luxun in his ancestral home (below), and (above) an excerpt from an essay by CaiYuanpei that considers the origins of religions, which was formative in Lu Xun’s own writing. [Photo by Jacob Pagano/chinadaily.com.cn]

It was perhaps out of his experience in this tradition-laden space that Lu Xun decided China needed not only a different literary sensibility, but a refashioned language in which to convey it.

LuXun began charting a life outside of this world from an early age, and studying at a several universities in Hangzhou, before moving abroad to Japan and Germany, and eventually returning to China. His family’s own financial and legal misfortunes often led him to take up teaching jobs and study traditional Chinese works, yet throughout the 1920s he published journals and essays that spoke to a radically new sensibility.

Indeed, even in his childhood, he often focused on study outside the core curriculum of classical Chinese, including folklore and mythology. He often studied with a servant in the house outside of class time, and the tales she told him would later become formative parts of his prose works.

Of the many plaques in the residence, one tells us that Luxun was often late to class and he was thus asked to carve the character “早,” or "early", onto his desk as a reminder of promptness. I bumped into someone while reading the paragraph, and we joked about the mandate. Then, the museumgoer looked up and said, "He wasn’t late, he was just listening to a different voice."

The moment was not unlike one of Xun's own stories, where small insights seem to hum like incisive commentaries. That Lu Xun found such voices, and recorded them for us in ways that spread through history, makes him not only one of the great writers, but one whom we surely should listen to today. And not just in quotidian moments, but also when we ponder the existentialquestions he crafted so lucidly.